This is a story with a lot of different threads. It’s about people I know and love (and knew and loved). It’s about inequities and the things being done to try and fix them. It’s about seeing what has been in front of our eyes all along. It’s about cross-sectoral social change.

It’s not a story with a happy ending. It is a story that is still being written and could go either way. Because, really, it’s a story about the re-founding of the State of Israel and the rebirth of Zionism — a radical reimagining of what sovereignty looks like here.

Here goes…

Ten years ago, during one of the many rounds of fighting between Hamas and Israel, I called an elderly cousin who has long since passed. He was a Jew from the former Soviet Union who had survived Stalin’s gulag as a young boy and moved to Israel as an old man.

I called him because then – as now – Israel was being bombarded by rockets and I didn’t know what else to do except check in on him. The call didn’t last long; he didn’t feel much like talking. But he wanted me to know what it was like whenever the missiles targeted his town (which was fairly often).

He explained to me that he did not have the physical ability to run down the many flights of stairs from his apartment and reach the nearest bomb shelter. And so, when the air raid siren would sound, he and his wife would sit together on their couch, quietly, just holding hands.

I’ve been thinking a lot about my cousin in recent months. In my previous post, I referenced a seven-year-old girl, Amina Hassouna, who was critically injured by the Iranian attack on Israel. One of Iran’s ballistic missiles was intercepted, blowing up in midair, and raining debris down below. A piece of shrapnel fell on her home, critically wounding her. She is still fighting for her life.

Amina is a member of Israel’s Bedouin community. The Bedouin are the largest group in Israel’s largest region (the Negev). They are the youngest demographic in Israel, the fastest-growing demographic in Israel, and they are (and not by a small margin) the most socioeconomically disadvantaged group in Israel.

The Bedouin have been hit hard by this war. Hamas murdered many Bedouins on October 7th, took others hostage, and also bombarded their homes with indiscriminate rocket fire. In fact, some of the very first people to be killed on October 7th were Bedouin women and children (including four kids from the same family). They were murdered in rocket attacks and what makes it all the more enraging and all the more unforgivable is that these Bedouin children, like Amina, might have escaped harm if they’d only had access to bomb shelters.

Many Bedouin live in the so-called unrecognized villages – i.e., shantytowns erected without proper permits. Those areas lack (legal) access to basic infrastructure. Internet. Electricity. And… bomb shelters. There aren’t private bomb shelters in the ramshackle hovels that make up the unrecognized villages. And the State has not installed shelters in those areas either. And when terrorists – whether Iranian or Lebanese or Palestinian – rain rockets down on Israel, the Bedouins have literally nowhere to hide.

The lack of shelter is a problem affecting Israeli society as a whole. Every single one of us lives in the shadow of Iranian, Palestinian, and Lebanese missiles. But not all of us have sufficient access to shelter. Some of us are lucky to have bomb shelters in our homes. Some buildings have communal shelters in their basements. There are also public shelters in various places across the country. But these are by no means sufficient to meet the problem, which has persisted for years thanks red tape, neglect, supply-chain issues, and insufficient capacity.

Again, this is a problem that affects all Israelis – my cousin’s experience is unfortunately far from atypical. But at the same time, it is a problem that is inarguably amplified and intensified in the context of Bedouin society. And so it’s critical that we think about the problem in the context of Israel as a whole, while at the same time giving due consideration to its specific manifestations in the context of Bedouin society.

I was sent a video by a friend, filmed during the very first days of this latest war. It’s not easy to see, but it’s important to watch it if you can — with the volume on [but please note that the audio includes air raid sirens and the sound of explosions]:

We are fortunate to have a relationship with two remarkable leaders – Dr. Muhammad Al Nabari and Itzik Zivan – who have built a singular and extraordinary platform: Yanabia. Yanabia works to secure a brighter and more equitable future for Israel’s Bedouins. Yanabia has incubated programs to combat unemployment and childhood hunger (simultaneously!), worked to provide access to lifesaving vaccines during COVID-19, and so much more. Bomb shelters aren’t usually within their purview, but – after October 7th – with lives on the line and so much at stake, they sprang into action and charged into the breach.

It started with concrete pipes.

In recent years, NGOs have been installing mobile bomb shelters throughout Israel. These consist of large, reinforced concrete pipes – with large cement slabs on either end. They can fit about 15 people at a time. It is no exaggeration to say that these things have saved many lives.

And within days of the October 7th massacres, Yanabia – with the backing of a handful of foundations – worked quickly to secure as many of these pipes as it could. It began working to install them throughout the unrecognized villages, in areas that were thought to be at higher risk of being targeted.

The government – yes, this government! – took notice of these philanthropic efforts and also pledged to invest in safety infrastructure for the Bedouin community. Dozens of shelters were deployed within days – providing immediate protection for Israel’s most vulnerable citizens. The children who were hiding under scraps of metal were literally dancing inside the pipes.

And before long, concrete pipes gave way to an even more creative and cost-efficient solution. Our friends and teachers at Yanabia quickly figured out that if you bury a shipping container in a deep hole, cover it with a meter of sand, suddenly, you have a perfectly functional bomb shelter. It costs half the price of a reinforced concrete pipe and it fits almost four times as many people. And so Yanabia and its partners worked to deploy this radical solution throughout the Negev, ensuring that thousands of people would be safe from Hamas and its missiles…

And if that weren’t enough, our partners in the Bedouin community even donated some shipping containers to neighboring kibbutzim, to ensure that their Jewish neighbors would be better protected from rocket attacks.

I said at the outset that this isn’t a story with a happy ending. It is unconscionable that it took the death of Bedouin children to get other people to pay attention, briefly, to just one aspect of the Bedouin community’s lived experience. And what happened to Amina Hassouna drives home quite vividly that whatever good has been done… still isn’t nearly good enough. And all the while, the gaps are growing. Statistics don’t have the same immediacy as a video of small children ducking for cover under pieces of cardboard and corrugated metal…. But please try to consider the fact that even before the war, seventy-four percent of Bedouin women were unemployed. Please consider how that is affecting not only their community, but also the Negev, and Israel as a whole. And please believe me: This is just the tip of the iceberg.

And so I’ll confess it’s a little hard to know how to end this. It rings a little hollow to ask for donations, or try to distill efforts to provide shelters to the Bedouin into easily digestible and broadly applicable lessons for changemaking and philanthropy. I don’t think it works quite like that… especially as the story is still unfolding in real time.

But I do believe this:

If we are to re-found the State of Israel, it won’t be enough to see what we should have seen already… to notice that which is right in front of our eyes. It likewise won’t be enough to do what we usually do. Programmatic responses that seek to close the gaps, improve equality of opportunity, and drive more equitable opportunities are vital and necessary but insufficient to meet this moment. We built bomb shelters to protect against rockets from Gaza. And now we have to contend with Iranian ballistic missiles. Which is to say, the problems are growing exponentially and I fear that the current technology of changemaking isn’t able to keep pace.

There are – thank God – remarkable leaders, across a wide range of sectors and communities, who are working seriously on building a different future for the Bedouin, for the Negev, and for Israel as a whole. And so I see it as our solemn obligation to try and accelerate those leaders, to put them into network with one another, and to help them develop new products and build vital infrastructure.

And to complement these efforts, we need an entirely new technology of changemaking, an entirely new approach to investing in social impact, and perhaps even entirely new way of thinking about politics and human society. I don’t have any answers just yet for what that might look like today, but I’m learning and I’m studying… and I intend to share what I find as that process unfolds…

Many of us are celebrating Passover, which marks when the Jewish people left the familiarity and relative comforts of Egypt – the superpower of the ancient world – for uncertain and distant shores: Along the way, amidst the harshness of the Sinai desert, they became a nation. David Ben Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister and an careful student of history, understood this well: He prophesied that the future of Israel will be determined by the Negev… a future that, in turn, will be determined by how Bedouins and Jews meet this moment together.

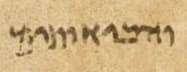

Because the Jews and the Bedouins are, at the end of the day, shutafei goral – two groups bound together by fate and destiny. And it is our shared and singular blessing that we get to try to write a future together.