An old woman lived alone in a small apartment. She had no family and she hadn’t accumulated much by way of possessions. The only thing that she had which mattered to her in any real sense was a small songbird. It brought her great joy and this old woman was determined to also share that joy with others. She would leave the birdcage by an open window — so that her neighbors and the kids playing below could hear its sweet songs.

There was a young boy who lived down the block. And he resolved to do something to hurt the old woman — not because he was especially cruel or especially hateful. No. He was just a kid. And he was just a human.

One day, while the woman was out, he climbed the fire escape and stole the bird through the open window.

The old woman came back to a quiet apartment and saw what had happened. She began to search frantically for her beloved pet. She knocked on doors. She put flyers everywhere. But nobody had seen her bird. Despondent, she sat alone in her empty home.

After a few days, the boy paid her a visit. The old woman opened the door and saw the kid with his hands clasped tightly together.

“Old woman,” he sneered. “I have your bird. Tell me: Is it alive or dead?”

The woman looked into his eyes and knew immediately what was at stake. If she answered that the bird was dead, he would open his hands and throw the bird to the heavens. If she answered that the bird was alive, the boy would surely close his hands tighter and crush it. No matter what she chose, she would be left bereft.

After an interminable pause, she gathered herself, looked the boy in the eyes, and replied, softly:

I don’t know. It’s in your hands.

My dad shared this story with my brothers and me one Friday night, as we sat gathered around the Shabbat table. He never told us how the story ended; that would have defeated the entire purpose.

I had always thought that I was meant to identify with the boy in the parable. That it was a tale about power and how to use it. That it was a lesson about how to use our God-given agency for good and for high purpose. It’s in your hands.

The society in which I was raised stresses how we are, in fact, created in God’s own Image. Even the most avowedly secular institutions and systems I once inhabited emphasized how each individual human is endowed with omniscience and omnipotence. This is the essence of the American liberalism of my youth: Each of us is a god unto ourselves; each of us is the main character; each of us is the center of an entire universe: Fill the earth and subdue it — it’s in your hands.

And if you’re steeped in this rhetoric and this way of thinking, you grow up with the expectation that you will one day wield godlike power; that you will one day grow up to be the boy in the parable — that the fate of the bird will rest in your hands.

But then you leave home and you discover just how powerful you really are. Yes, humans can do extraordinary things, but when all is said and done, there is only one God… and it’s not us. You discover that adulthood is not tantamount to godliness — at least in the sense of endless horizons, untrammeled possibility, and mastery over life and death. Adulthood, as it turns out, entails a great deal of self-restraint, compromise, and relinquishing (i.e., godliness of a different sort). Independence is just a fancy word to disguise how very dependent we are on others — as with adults, so too with countries.

Feeding your children, building your home, living your life, stocking your shelves, protecting your cities; none of these are things that are entirely (or even mostly) within our control. We are so incredibly reliant on the decisions of others: The kindness and the caprice and the cruelty of strangers, friends, and everyone in between.

As I write these words, I understand my dad’s parable very differently. I’m not the boy. I’m the old woman: The bird — everything I hold dear — is the hands of others.

The world that you and I will wake up to will be determined by the choices of others: Generals, clerics, and politicians. Some of them sit here in Israel. Some of whom sit in their halls in Tehran. Others are huddled in rooms in Washington, D.C., in Abu Dhabi, in Riyadh, in London, and everywhere in between. Some of them are accountable to me as a voter. Some of them have my best interests at heart. Some of them couldn’t possibly care a whit about me. Some of them would very much like to see me dead.

That last group of people is vaporizing apartment buildings throughout my country; they’re not doing this to gain military advantage or because these are legitimate targets under the laws of armed conflict. They’re just trying to take as many of us with them as they can. My country has systems and structures and considerable resources at its disposal to prevent that from happening — but these are not guarantees.

The sky is lit up with missiles; the windows are rattling from interceptions; the ground is shaking from impacts.

And at the end of the day, I have no real influence nor control over how this is going to play out.

Is the bird alive or dead?

I don’t know. It’s in their hands.

I hope they’ll choose wisely.

The old woman in the story is also powerful.

I don’t mean to suggest that she has any control or influence over her antagonist, inasmuch as she has the ability to confer absolution or condemnation or even to make him pause. However you believe the story ends, there’s a real chance that — whatever he did — this boy walked away from that final confrontation without a second’s thought.

Rather, the old woman had power over herself.

When faced with a situation in which it was genuinely beyond her control, she did not beg. She did not plead. Outwardly, at least, there was neither denial, nor anger, nor bargaining, nor depression in her affect. Nor, for that matter, was there passive acceptance.

Rather, she looked her counterpart in the eye and she confronted him with quiet dignity, gentle wisdom, and respectful challenge. It’s in your hands.

This was not an old woman throwing herself upon her tormentor’s mercy. No — this was a radical act of transcendence.

The boy had set a flawless trap for her: Either choice would be to her disadvantage. And so she refused to play an unwinnable game. She refused to engage on his terms. She ascended beyond his plane.

That is power of a different sort. That is true power — gevurah, or self-mastery — the kind that is central to ethical living in traditional Judaism. It is the sort of power that renders you immune to the slings and arrows and bullets and ballistic missiles that the world tries to throw at you.

That’s not to say they don’t hurt — they can and they do. That’s not to say that they don’t kill — they can and they do.

But they cannot destroy and they cannot damn.

… And what of the bird?

I doubt that its song changed at any point during the story.

Because the bird didn’t sing to make the old woman happy. It didn’t sing that it might move the young boy to spare it. It didn’t sing for any reason other than it was a bird and birds (like happy people) sing.

Which is rather like my people.

***

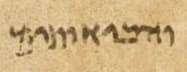

On most major holidays, Jews traditionally recite Psalms 113-18 — a liturgy known as Hallel. In the synagogues I frequent, these are usually sung with great fervor and ecstasy — because Hallel is typically considered a cathartically joyful prayer.

The Talmud records a debate over the origins of Hallel: Who was the first to recite it and under what circumstances? One sage suggests it was Moses at the Splitting of the Sea; another posits it was Joshua; other candidates include Deborah and Barak, King Hezekiah and his court, Daniel’s companions in Babylon, and Mordechai and Esther.

And with deepest respect to my ancestors, the particulars of the debate aren’t what’s interesting. I find the disagreement compelling only inasmuch as it shows an absolute, wall-to-wall consensus: Every single rabbi agrees that Hallel originated not as a prayer of celebration but as a plea for deliverance.

“Not for our sake, O Lord, not for us!”

The Jews, in their hour of peril, recited these prayers with their enemies bearing down upon them; and then, after their miraculous victory, they recited those exact same words in thanksgiving.

“No — the dead will not praise God; nor will all those who descend in silence.”

Hallel is a text and a melody that doesn’t change with the external circumstances. Rather, it’s a constant — a musical ostinato, an idée fixe — that shows up before, during, and after a crisis. Is it a cry for salvation? A wish fulfilled? An unanswered prayer?

Yes.

We sing Hallel when the walls are shaking at night and we sing Hallel if the sun rises the following morning. Not because we think it will save our lives. Not because the relationship between humanity and God is transactional.

No, we just sing.

Thirty years ago, my dad told me a story. I thought it was a warning and admonition about how to use the privilege and power that we’re given. It is. But that’s only one layer to the story.

Because really, each of us is the young boy, the old woman, and the bird all at once. Isn’t that the human condition? The fate of others sits in our hands and we must use our power wisely. Our fate rests in the hands of others but we can still transcend.

But most of all, our children sleep fitfully beside us while we rub their backs — whispering gently to them and singing the song of our fathers in hushed tones, hoping that we’ll have the privilege to sing it again loudly the next day:

Hallelujah.

It is a fortunate son who was read to before bedtime. I don't remember that so much, I do remember playing board games with my father, who could laugh, play, enjoy and live life differently than my Auschwitz-surviving mother could.

It is a fortunate father who can read the beautiful and poignant memories that his son so well describes.

This Father's Day we all can pause to appreciate the unique qualities with which we were gifted from our dads. It is all in our hands: no matter from whose point of view, no matter from which perspective. We age, hopefully we still grow, and if we are very lucky we also get another chance to get it right, or at least better.

I did love reading with my children, not as many chances to read to my grands. Yet.