In the tenth chapter of Leviticus, Aaron loses his two oldest sons – killed in the line of duty. But immediately, Moses tells Aaron (who witnessed the horrible scene) that he may not mourn his sons. Aaron is, after all, the High Priest: He is irreplaceable and has a critical job to perform… one that is incompatible with mourning. And so Moses commands Aaron to restrain himself, withhold his tears, and forgo any sort of visible sign of mourning. Aaron is left to stick to his post. But Moses assures him that the Jewish people will take responsibility for mourning Aaron’s two sons: “and your brothers, the House of Israel, will mourn the conflagration that God has wrought.”

Tonight marks the start of Yom HaZikaron — the day on which Israelis gather to mourn the tens of thousands of our brethren who fell in the line of duty while protecting this country, and the many civilians who were murdered in the many wars which have characterized this country’s history. This year, the ranks of the bereaved have swelled — there is not a single Israeli who is unscathed by this war.

Unlike in Leviticus, since October 7th, there has been no division of labor between serving and grieving. Mourners haven’t been exempted from service. Those serving haven’t been able to desist from mourning. All of us have had to do both simultaneously. We are all Aaron and we are all the House of Israel all at once. The families of the hostages continue to travel the world, crying out desperately to be heard – never pausing for a moment, even amidst their grief. Survivors of massacres returned to their posts almost immediately (as one of them put it: “My patients are counting on me.”). People who are sick with worry and grief and anger are still waiting tables, driving taxis, drafting term sheets, running Zooms, and everything in between.

It’s been more than seven months since the war began. This country has been running an ultramarathon at a sprint’s pace. We are collectively just as brokenhearted as we were on October 7th. But it’s been compounded by seven additional months of exhaustion, of trauma, of air raid sirens, of funerals, of shivas.

But tonight — Yom HaZikaron — is sacred time, culminating with a two-minute siren tomorrow morning. The entire country will come to a halt to stand in silent reflection. For too many of us, this will be our first moment since the war began to pause briefly from holy service – and simply grieve. To rend our shirts. Bare our heads (and hearts). Weep. Breathe. Remember our loved ones.

And then, back to work.

I wrote what follows on the tenth day of the war, making it something of a time capsule… a window into the immediate aftermath of the October 7th massacre, or — at least — my experience of it.

I hope those of you who have seen it already will forgive my re-sharing it. I offer it in advance of Yom HaZikaron, first, as a meditation on the grief universally observed (but unequally distributed) by the people of Israel. And I also offer it as a partial answer the question to my question from last week’s post: “what have you seen that makes you want to be part of this?”

October 17, 2023

I haven’t been able to write anything particularly coherent, let alone eloquent, about the experience of the last two weeks. It’s like someone shattered a vase and I’m trying my best to somehow reconstruct it by just pointing at the shards. How can I possibly capture the totality of these last few days? How does anyone possibly make sense of it all – each headline, each video clip, each photograph, each account of Hamas’ atrocities?

The calm of a holiday morning shattered by sirens. Watching families walking to synagogue, dressed in their festive holiday clothes, instantly pick up their small children and sprint to bomb shelters. Seeing my religiously observant neighbors tearing down the roads at breakneck speed, driving off to join the battle and rescue the families from the ongoing massacre. Sheltering behind a low wall with my kids when we were caught outside during a barrage of rockets, as grown men lay trembling next to their parked cars. Fluctuating between suffocating dread, anger, grief, horror, sadness, hypersensitivity, and numbness. Trying to sell a night in the bomb shelter to my children as a fun sleepover, and not a potentially life-saving measure. Resuming Zoom school. Hourlong lines in the grocery store. A person I’ve never met before outrunning me to my own child, scooping her up, and sprinting with her to a bomb shelter. Listening to a cab driver get a call from their kid deep behind enemy lines… imparting what might be a final piece of advice, saying “I love you,” perhaps for the last time.

***

But maybe, just one story.

It must have been on the first or second full day of the war that a friend forwarded me a note on WhatsApp: The family of a missing girl was trying desperately to get the attention of a specific Western government. This girl had been at a music festival in southern Israel that had been transformed into a living nightmare:

Palestinian terrorists invaded Israel and unleashed horrors that defy comprehension and description. Hundreds of peace-loving people were slaughtered in cold blood; women raped on top of their friends’ corpses; survivors tortured, abused, and then taken to Gaza. And not far away, more terrorists were burning Jewish families alive, decapitating babies in their cribs, killing parents before their children’s eyes, and killing children in their parents’ arms. The human soul cannot possibly comprehend the extent of the evil, the savagery, the inhumanity that was inflicted on these people – my people – on Simchat Torah 5784, on what was supposed to be a day of pure and uncomplicated joy and rejoicing.

This girl’s family had last heard from her in the midst of the carnage, and they had strong evidence that she had since been taken to Gaza. The prevailing wisdom was that Hamas was less likely to harm dual nationals and foreign citizens. Although one of her parents was a dual national, the young woman herself was not. And as a result, this foreign government wasn’t giving her family much attention or prioritizing her in relation to its other citizens affected by the war.

The family was desperate: Could someone, anyone, please help?

I didn’t know the missing child, but I did know someone connected to the government in question. That person was more than willing to help put me in touch with someone even better connected. Over the following days, people who did not know me – let alone the family – moved heaven and earth on behalf of this young woman. And those efforts, together with others, bore fruit: Elected leaders and prominent voices took notice of the case. And in the end, the family began to get the help they needed. This went on for about a week. It was nothing short of miraculous. There was even reason to hope that she would come home.

And then, late one night, her family received word: Her remains had been located and positively identified.

She had been dead since the very first day of the war.

***

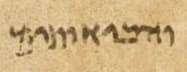

Mi she’nafla alav mapolet – safek hu sham, safek eino sham; safek chai, safek met … m’phakim alav et ha’gal.

If there’s an earthquake, an avalanche, a rockfall, and you believe someone is trapped beneath the rubble – you dig them out. So says the Talmud. Doesn’t matter if it is Shabbat or a Yom Tov. Doesn’t matter if the person in question is an insider or an outsider, whether they’re a member of your community or not. When human life is at stake, you do what you need to do to save it. You start digging.

If there’s an earthquake, an avalanche, a rockfall, and you believe someone is trapped beneath the rubble – you dig them out. It’s not clear whether they’re still breathing or whether they’re dead… in fact, it’s not even clear if there’s someone in there at all – you keep digging all the same. You keep digging until you have exhausted yourself, until your fingers are raw and bloody, and you’ve violated the laws of the Sabbath fifty times, a hundred times, a thousand times over. And then you dig some more.

You keep digging until you know for certain that the person is dead. You dig and you dig until you’ve looked them in their unblinking open eyes, listened in vain for their heartbeat, and exhausted every possible avenue. You dig until you’ve cradled them in your arms and until you know in your heart of hearts that there is truly nothing further that you can do for them.

And then you start trying to save the next one.

***

Around me, an entire nation is digging frantically. We are digging because there are nearly two hundred of our own – grandparents, parents, friends, nieces, nephews, siblings, cousins, babies, toddlers – held incommunicado in cruel and inhumane conditions by a genocidal death cult. We are digging because tens of thousands of Israelis have become refugees in their own country, thanks to relentless and constant missile attacks from Palestinian and Lebanese terrorists – and those people need food and shelter, medication, and psychological counseling. We are digging to ensure that this country’s supply chains, labor force, and infrastructure are capable of withstanding a far-reaching and prolonged war. We are digging to get people off of the sidelines and involved in this generational reckoning.

We are also digging in to prepare ourselves for the coming onslaught. And make no mistake about it: Terrible things are coming. We will have to fight, hard, to try and rescue our friends and family from the clutches of the genocidal death cult that sits on our borders. We will have to fight hard to dismantle evil institutions and organizations in order to ensure that they will never again threaten innocent life.

Too many will vilify us for having the temerity to try and live in our homeland, for trying to protect our children, for refusing to die. And so, we are digging in to prepare for that.

But we are also digging in a much more literal sense. We are digging through the wreckage of the massacres and the missile attacks to uncover what remains. And yes: Teenagers – children – are volunteering to dig graves in the cemeteries.

***

The funerals also defy imagination. More than one thousand Israeli civilians have been massacred, along with hundreds of soldiers. Each one of them had a name and a face, hopes, dreams, stories, and a smile. And now one by one, they are brought out covered in a burial shroud, and laid before their heartbroken friends and family.

One wouldn’t think it possible for human beings to scream like that, for human beings to cry like that or make noises like that. But they can.

“Aich hem asu lach?” What have they done to you?!

But even as the families’ shrieks shake the very foundation of the world, the mourners – wracked with sobs – somehow find the strength to sing. They sing to the body of their child; their brother or sister; their mother or father; their niece, nephew, or cousin; their grandparent or great-grandparent. A favorite song. A favorite hymn. An anguished prayer. They sing as they bear their loved one’s body to the grave. And they sing as they put them in the ground.

But then there’s a moment of silence. And the assembled mourners pick up the shovels and fill in the grave. And the only sound is the sickening scrape of metal against gravel and dirt, as we cover up another person to await the End of Days.

***

We are digging because we are broken-hearted. We are digging because we are not broken. We are digging because we must dig a new foundation for our homeland. Around us, the nation is being born again. The State of Israel is being re-founded and rebuilt before our very eyes.

We are in a position to write a story very different from the one we’ve been writing for the last seventy-five years. There is reason to believe we may yet pull this off. But it’s by no means guaranteed. Ego persists. Small-mindedness persists. Fear persists. It is possible the forces of inertia and the status quo will win out.

And if they do, may God help us. May God have mercy on us.

But all around me, there are reasons to believe we might yet get this right. There is evidence that we might yet build something truly radical and novel in an age of polarization and zero-sum politics. Not a shtetl, or a mellah, or a Soviet commune, or an American suburb transplanted into the Israeli soil. Not a balkanized array of cantons, an enforced orthodoxy, or even a melting pot. No. We are seeing the emergence of something that leverages the heterodox pluralism of Jewish experience and the best of the democratic tradition – a state founded on mutuality, capacious enough to encompass different identities and narratives. Each individual and each group puts its best self on the line, each sacrifices something, and we’re all better for it.

The same Israelis whose hands were around each other’s throats two weeks ago have now wrapped their arms around one another in tight and tearful embrace. Haredi Jews have put down their sacred texts and are volunteering to keep the economy running while the rest of the workforce has been mobilized for war. Jewish Israelis are partnering with Arab Israelis, mobilizing to purchase and install hundreds of mobile bomb shelters to protect those who would otherwise lack access to them. Muslim Israelis are stepping up to give comfort and support to their grieving Jewish neighbors. And we can see evidence of this new reality abroad, too: There are herculean efforts to provide humanitarian relief for internally displaced Israelis, funded by Jews and Christians from all over the world. People are working around the clock to airlift in essential supplies and personnel. And American Jews and their allies are starting to draw a line in the sand, to show that there might actually be consequences for moral equivocation when it comes to the wholesale murder of Jewish babies and rape of Jewish women.

This is a start – but it’s only that: A start. The full extent of the carnage is not yet known. The war still remains to be fought. And when it’s over, entire communities will need to be rebuilt. We will need to build new institutions, new civic and social infrastructure. The Israeli future, the Jewish future, and nothing less than the future of humanity itself, depends entirely on our ability to sustain these efforts and to keep on digging – no matter how painful it is and no matter the condemnation we receive.

Because that’s what this moment demands. Bring a shovel or use your hands. There are lives that need saving. And we need you to dig.