“Our noise for some seconds passed beyond excitement into a kind of immense open anguish, a wailing, a cry to be saved. But immortality is non-transferable. The papers said that the other players, and even the umpires on the field, begged him to come out and acknowledge us in some way, but he never had and did not now. Gods do not answer letters.”

- John Updike, “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu.”

I.

The Torah has a lot to say about sacrifices — what you bring, why you bring it, when you bring it, how it gets slaughtered, and so on — but at bottom, a sacrifice in the context of Judaism really just boils down to this:

You’re a subsistence-level farmer, whose wellbeing depends on unpredictable meteorological phenomena. At regular intervals throughout your life and for a wide variety of reasons, you make the lengthy trek from your ancestral home to Jerusalem with something valuable in tow: You bring along a goat, a lamb, or a dove — something on which your family’s survival may very well depend. That animal could put meat on your table, milk in your cup, eggs in your pantry, or clothes on your back. And when you get to Jerusalem, you hand that animal to a priest, who takes it, kills it, and puts it on the altar.

You watch that animal go up in smoke.

And then you go home.

You’re not taller, thinner, or better looking. Your house is still the same size as it was before. The sun continues to rise in the east and set in the west; and the laws of nature continue to operate just as they always did.

So it goes.

Being a rational and thinking person, why would you bother with all of this? Do you believe that your giving up something precious has a tangible effect on your material wellbeing? Do you sacrifice your firstborn animals because you think it will bring you more animals? Do you give up a turtledove because you believe it negates that bad thing you did that one time?

Maybe.

But if that’s the motivation behind handing over a (literal) cash cow and watching it go up in smoke, then let’s be clear about our terminology: That’s not a sacrifice — it’s an investment.

We understand intuitively that these words are not synonyms. When you make an investment, you typically give up something in the hopes of getting more of that selfsame thing; you expect to earn back what you’ve given up, and then some. Here’s some money, now go earn me more of it. I’ll spend my time on this task, so that I can later spend my time on things I’d rather be doing. There is nothing wrong with that whatsoever; but call it what it is: It’s classic reward-seeking and transactional behavior — it’s an investment.

Perhaps bringing animals to the Temple was — in the eyes of my ancestors — an investment strategy of sorts. Here’s some of my produce; I hope next year’s harvest is even better. Here’s a goat; please give me more goats. Take my crops; please don’t smite us in a plague. And who’s to say that they were wrong? I genuinely don’t mean to sound dismissive: Perhaps those rituals did pay off in that sense. I truly don’t know.1

But I stubbornly insist that there is a difference between investments and sacrifices. I do not believe that all human activity can be reduced to psychological egoism,2 I chafe at reading the Torah as a Hebrew predecessor of Poor Charlie’s Almanack, and I am uncomfortable with conceptualizing the Temple as purely a place of metaphysical commerce.

There has to be something else at play.

II.

Start with the word itself.

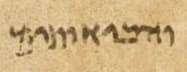

What we would call a sacrifice in English is — in Hebrew — called a קרבן [korban]. The verb for bringing a sacrifice is — in Hebrew — להקריב [le’hakriv]. Both terms are derived from the root ק-ר-ב [k-r-v] which signifies drawing closer or coming near. And that is precisely the point. As the great Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch put it: The purpose of a קרבן is to seek God’s nearness … which for a Jew is the sole good.3 The act of bringing a korban is — as Jewish tradition wants us to understand — an attempt to try and seek intimacy with God.

But if we’re being theologically rigorous, we ought to understand that this isn’t merely a quixotic undertaking — it’s an impossible one. Jewish theology teaches us that God is transcendent and while there might be ways in which humanity can interact with God, at the end of the day, God is always out of reach. There is an unbridgeable gap between humanity and God. We yearn for proximity and we try our best to get a little closer to God, but we know there’s no hope of ever truly attaining this goal: For no person can see Me and live.4

Thus, the act of bringing a korban is the act of relinquishing something in pursuit of a goal that you have no hope whatsoever of actually accomplishing. It’s embarking on a project you know that you — or anyone else, for that matter — has no chance of even coming close to completing.

This, in turn, dramatically differentiates a sacrifice from an investment. Some investments are risky — extremely so, even; they can (and often do) go to zero. But an investor does not intend that to happen; an investor makes a calculated risk, and will often take steps to make his or her investment more likely to succeed. A korban, by contrast, is made knowing at the outset that we’re going to fall short. We sacrifice in service of something that is beyond anyone’s individual or collective power. A korban is made in pursuit of a goal that is both practically and theoretically out of reach. We seek intimacy with God: Whose presence is deeply felt, yet remains always and asymptotically beyond us.

To bring a korban, then, is a seemingly irrational thing to do. Again, we’re taking food off our table, clothes off our back, money in our pocket… and we’re literally setting them on fire. We don’t do so because we expect to get more food, more clothes, or more money. We do it in furtherance of a goal that is by definition never achievable. We’re not expecting to see a meaningful or tangible reward. Sacrifice in the biblical sense is not about a hoped-for return. It’s about relinquishing, giving up, and letting go. And it’s about doing so in the hopes of moving incrementally closer to an unattainable Destination.

III.

Investments are made because you want to grow your assets — because you want to see more of something. A Biblical sacrifice is all about relinquishing something certain, tangible, and valuable… and doing so for the sake of a conceptually impossible and unattainable goal.

And in this respect, the sacrificial cult cultivates the polar opposite of an investor’s mindset: It forces us to let go of things that are precious or things that matter deeply to us — without any expectancy or hope of a material “return.”

That being said, mine is not an ascetic religion. It stands in marked contrast with traditions that valorize renunciation, hermeticism, monasticism, or the like. The Talmud, for example, is clear on this point: When we are called to stand before the Almighty in judgment, we will be compelled to give a detailed accounting for every permissible pleasure that we denied ourselves.5 And I likewise see the Law as balancing two competing imperatives — seeking to ground us in this world, while also ensure that we’re not distracted by the bright and shiny things which fill it: Work hard and enjoy what the world has to offer — but do not forget for an instant what actually Matters.

And thus, korbanot are — as Rabbi Hirsch admonishes us — not meant to be pointless, nihilistic, or masochistic exercises in “destruction, annihilation, and loss.”6 But it seems to me that korbanot are not free of pain. You come to the Temple because you have an unquenchable desire for intimacy with God… and you leave without having nearly begun to slake your thirst. In the process, you take a sure thing — something you’ve tended to, cared for. Then watch as it’s killed before your eyes and goes up in smoke.

… Does that make us freiers?

I surely don’t think so. But it would undermine my own point by talking about the positive value of self-negation. That is (and at the risk of getting too meta), if I argue that there are positive consequences that accrue from having cultivated a sacrificial mindset, this risks transmogrifying sacrifices into investments.

So perhaps therefore we ought to stop there. Or perhaps maybe the point is that there is something paradoxical about korban: It is simultaneously and entirely both investment and a sacrifice. Or perhaps all that needs to be said for now is this:

אוי מה היה לנו. Ah, what we once had.

There was once a Place where we could stand — whether as individuals, whether as a community, whether as a nation — and where we could try to thread the needle of being grounded in this world without being mired in it. There was once an Institution that allowed us to contemplate the awesome and ineffable transcendence of God and where flesh and blood, bone and sinew, could dream the impossible dream of moving incrementally closer to an unreachable Destination.

But we don’t have that anymore. And we’ve become so acculturated to this reality that we’ve not only normalized our diminishment but perhaps we’ve even embraced it.

אוי מה היה לנו. Ah, what we once had.

IV.

If — like me — you hold fast to Jewish religion, in the absence of the Temple, we’re left only with prayer. And the question becomes how we can use prayer to try and compensate for what we’ve lost.

At times, I fear that prayer is a poor substitute for what was taken from us. That’s chiefly because talk is often cheap — certainly compared, at least, to putting something on the altar. Watching a key portion of your livelihood go up in smoke is an entirely different experience than softly beating your breast and reciting, in hushed tones: we have become guilty, we have betrayed, we have robbed.

It just isn’t the same.

But I still see in prayer echoes of the sacrificial cult. Because even if prayer doesn’t hit our wallet per se it does actually have a material impact on single most precious and finite human resource: Time.

We pray for healing. We pray for peace. We pray for justice. We pray for redemption. We aren’t praying with the expectation that our words will affect God — but we are praying because we desire closeness and proximity to God… knowing full well how impossible that is.

The time we spend in quiet contemplation or in fervent recitation — that’s time that we could be using for literally anything else. Every minute spent in prayer comes at the expense of productivity — we’re not writing emails, we’re not checking the news, we’re not playing with our kids… heck, we could literally be working to bring about whatever it is we are praying for.

Instead, we’re sacrificing a scarce resource. We’re taking a sure thing — seconds, minutes, and hours that we don’t have — and we’re giving it up: Not in expectation of material benefits, not necessarily consciously seeking intangible benefits either, and surely not because we expect to slip the surly bonds of earth.

No. We just do it.

And then we go back to work.

V.

King Solomon admonishes us: Remember your Creator in the days of your youth — while the time of evil has not yet come, and the years will come when you will say “I have no delight in them.”7

A few generations after the Romans suppressed what remained of Jewish autonomy in the Land of Israel, a rabbi living in the Galilee shared a profound interpretation of this verse.8 Rabbi Joshua of Sakhnin taught in the name of Rabbi Levi that this verse encourages the Jewish people to seek out God from a position of strength — rather than one of diminishment. Remember your Creator while the priestly caste remains intact. Remember your Creator when the Davidic line remains in power. Remember your Creator while the Temple remains intact. And so on.

The reader, of course, understands that over the course of Jewish history — one by one — each of these things were taken away from us. Indeed, over the course of Jewish history, while our technological capabilities have grown, our list of covenantal assets has been shrinking. Prayer, for example, is an imperfect substitute for a korban. Sure, we have magical pocket computers. But we lack access to some of the most important pieces of Jewish communal infrastructure…the institutions and systems designed to facilitate a thriving, covenantal relationship with God have long since been destroyed.

The reader, of course, also understands that we lost these things due in large part to our own sins, mistakes, and choices. And so, in effect, we’re either stuck waiting for God to hit control-alt-delete on the historical process — or we need to somehow miraculously pull ourselves up by our own bootstraps.

This homily does, to some extent, foreshadow Captain Hindsight: The best time to have repented was three thousand years ago. And failing that, it would have been better to have repented two thousand years ago.

And yet the Talmudic exegesis strikes a hopeful chord amidst the sadness. Notwithstanding the fact that our balance sheet has been shrinking steadily, there’s always still an option to turn things around: Remember your Creator while you’re still around.

Do we have the Temple? Do we have sacrifices? No and no. But at least we have prayer.

Are our leaders worthy heirs to Aaron the Priest, King David, Rabbi Akiva, and the like?

Maybe. Maybe not.

But either way, we’re still here.

And for the first time in centuries, my people have independence, a homeland, and a State. And most importantly, we have each other.

Which means we have a chance.

And so all is not lost. Far from it.

Because we’re still here.

And either way (as my friends and teachers who have engaged with me on this topic rightly point out), even if sacrifices didn’t produce material changes in the offeror’s circumstances, there may very well be intangible or psychological benefits that come from sacrifices — a sin-offering assuages a guilty conscience and gives the offeror the ability to try and move on, a thanksgiving-offering provides a healthy outlet for gratitude. And so on.

And (not but) I also would observe that notwithstanding the efficacy of a sacrifice, there’s still an element of cognitive dissonance that accompanies the ritual. Consider, for example, a sin-offering. The ritual matters, yes; but it’s not as if it erases your actions or the event as it happened. And I have to imagine that our ancestors knew and felt that disconnect no less acutely than we do.

This is the notion in philosophy that everything we do is motivated by self-interest.

The Hirsch Chumash, Leviticus 1:2 (קרבן). In fairness, it is worth noting that Rabbi Hirsch vehemently opposes using the term sacrifice as a translation of korban — insofar as the translation “has taken on the connotation of destruction, annihilation, and loss — a connotation that is foreign and antithetical to the Hebrew concept of קרבן.” (Id.).

Exodus 32:20

Jerusalem Talmud, Tractate Kiddushin 4:12.

The Hirsch Chumash, Leviticus 1:2 (קרבן).

Ecclesiastes 12:1.

Eicha Rabbah, Prologue XXIV