From The Narrow Place

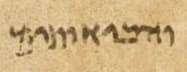

"And as for you, Daniel: Shut up these words and seal the book until the time of the End..."

“They justified, and destroyed, his life.”

- Jorge Luis Borges, Three Versions of Judas

The story is told of President Kennedy, who paid a visit to NASA after announcing his plan to send astronauts to the moon. He met with the scientists and engineers, he toured the facilities, and he delivered some remarks. As he was leaving, the President encountered an old man — a member of the custodial staff. Mr. Kennedy greeted him, shook his hand, and asked him: “What is it that you do here?”

Without missing a beat, the janitor responded: “Well, Mr. President, I’m helping put a man on the moon.”

Exactly so.

NASA would not be able to function without this man. By keeping the floors clean, the garbage cans empty, and the chalkboards untouched he was — in fact — helping put a man on the moon.

In like fashion, if you were to ask me what is it that I do, I would tell you honestly: “I’m helping prevent the coming of the Messiah.”

Allow me to explain:

***

It is an article of traditional Jewish faith that a Messiah is coming, that there will be a Resurrection of the Dead, and that the world will be somehow redeemed. These are nonnegotiable matters in the context of Orthodox Judaism; I am expected to believe in these things and to faithfully await them. And I do.

And for its part, the Talmud outlines two conditional pathways for the ultimate redemption:

And Rabbi Yochanan taught: The Son of David will not come except in a generation that is either entirely righteous or entirely guilty.1

That is, the Biblical texts concerning the End of Days and the coming of the Messiah appear to be sharply in tension with one another. Some texts indicate that the Messiah will appear as a lowly figure, riding on a donkey — others suggest that the Messiah’s presence will be announced through miraculous and wondrous signs. Some texts suggest that humanity’s pathway towards Redemption will unfold seamlessly and without friction; others suggest that it will be presaged by untold apocalyptic horrors. One way that the Talmud attempts to make sense of these apparent inconsistencies is by suggesting that there are two possibilities for how humanity gets to its happily-ever-after2":

Ideally, we succeed in figuring it all out on our own. We banish iniquity; we overcome inequity; we do what we need to do. And in this case, the Messiah will appear simply as validation that our efforts have succeeded and as the culmination of all our hard work.

Less-than-ideally, we get to the End of Days via divine intervention because it’s completely and utterly hopeless to expect that we’ll ever get there on our own. We hit rock bottom and we need God to bail us out: You’ve tried, you’ve failed, now I’m taking over… but you’re not going to like it one bit. This is the Armageddon scenario… a possibility so horrifying to consider that you have Talmudic sages praying for death rather than seeing the Messiah come under such circumstances: Let the Messiah come; but please don’t let me be around when it happens.

***

Litigator that I once was, I cannot help but note the Talmud’s choice of words. Rabbi Yochanan did not say that the Messiah would appear in a generation that is mostly righteous or mostly wicked. Rather, he used unqualified and absolute language: History only ends in a generation that has it all figured out, or in one that is entirely, completely, and totally unworthy of redemption.

And if those are the two options, when I consider our present state of affairs, it’s awfully hard to believe that we’re going to bring the Messiah about through our collective righteousness — within my lifetime, within yours, or even that of our most remote descendants.

Can we look in the mirror and feel proud of ourselves? Look at the people we elevate; look at the leaders we follow. We are a generation content to elevate the corrupt, the feckless, the moronic, the hackish, and worse. Or simply judge us by the works of our hands: Look at the injustice festering in our neighborhoods. Is this a generation that’s closer to demonstrating complete righteousness or complete wickedness?

And what frightens me the most is the fact that humanity seems utterly incapable of learning from our mistakes or showing the capacity for collective self-improvement. The clearest proof of this is the complete and utter failure of anti-antisemitism as a strategy. We are within living memory of Belzec, Babyn Yar, Skede, Auschwitz, and Mauthausen. We have spent millions of hours and billions of dollars in the intervening decades to try and teach people to stop trying to kill Jews. And look what we have to show for it:

Consider the absolute idiocy and drivel being spewed by elected officials, so-called MacArthur Geniuses, best-selling authors, well-credentialed academics, and the like. Closer to home, I have former professors, colleagues, classmates, and even people I once considered friends who defend infanticide, mass rape and hostage-taking as justified resistance. Take all the barbaric yawping in defense of Iran’s proxies and the ignorant mobs howling about rivers and seas that they couldn’t find on a map if their very lives depended on it, and consider this alongside damning indifference to actual attempts at genocide, mass starvation,3 ethnic cleansing, and the like. Hundreds of thousands of people raped and murdered in Ethiopia. Christians in Nigeria being systematically slaughtered. Tens of thousands of Ukrainian children disappeared into Russia. The world says nothing (and does even less) in the face of real crimes against humanity.

The Holocaust was not a morality play for the benefit of humanity. My people did not endure two thousand years of violent antisemitism for the sake of making everyone else smarter, wiser, and more virtuous. And yet the fact humanity has completely and utterly failed to learn from the crimes committed at the expense of my people is damning and unforgivable — and the implications are quite troubling. If we cannot learn from this, what hope is there that we’re capable of learning anything?

I am not blind to the miracles that surround me. I write these words looking out at the Old City of Jerusalem, cognizant that I have been given blessings and opportunities beyond the wildest dreams of our ancestors. I do not wish to overlook the extraordinary good with which we’ve been graced or discount the progress that we’ve made. But oh God, it’s awfully hard to claim with a straight face that humanity is on an upward trajectory: At times, it seems we are so much closer to being a generation that is entirely condemnable, damnable, and guilty.

***

If this is so and if our mission is to bring about the coming of the Messiah, you might conclude that we ought to just give up. Stop trying. Stop doing the right thing.

Because every single tree we plant, every hungry child we feed, every refugee we care for, every bomb shelter we build, every struggling small business we stabilize, every good deed that we do… it has the practical effect of keeping humanity that much further away from hitting rock bottom. The well-intentioned among us are preventing the Apocalypse; and so long as they are at their posts, it means that History continues on inexorably. Trying to bring about the Messiah through good deeds means, practically, we will continue to defer the End of Days. Our effort to put the world back together ensures — paradoxically — that it will stay broken for that much longer.

… But of course, to give up would be monstrous. And thank God, this is not the Jewish view of things. Sparking the war of Gog and Magog, provoking Armageddon, and gleefully embarking on a race to the bottom would be — simply put — a Bad Thing. It doesn’t matter remotely what good sits on the other side of those trials and tribulations: Judaism abhors and condemns that way of thinking. Ends categorically do not justify means.4

And (not but) we have to be honest with ourselves and we have to consider the full effect of our well-intentioned actions. As much as we want to believe that everything that we’re doing is helping to make the world a better place, a holier place, a more just and equitable place… we are, at best, boats against the current when it comes to human nature and to the forces of history. When we make our lonely stand in defense of what is right, and we continue to try and do what is asked of us, perhaps all we’re doing — practically speaking — is forestalling the Apocalypse and therefore the Redemption.

***

The Existentialists pondered the fate of Sisyphus, the mythical Greek antihero, condemned to labor for eternity at a task that was as impossible as it was meaningless. A friend, teacher, and mentor, commenting on this myth, remarked with genuine envy: Lucky guy! He gets to try and push a rock up a hill… every day!

Our fate is even more strange, terrible, beautiful, and extraordinary. We are told to build a redeemed world, even if it means that our very attempts to do so put that selfsame goal further and further out of reach.

And so when I am called to account before my Creator and I am told to answer for my actions — I will, I pray, be able to stand up with a smile on my face and to answer proudly that I did everything I could to ensure that this world stayed only partially broken, at least for a little while longer.

There’s no shortage of ways that we can prevent the war of Gog and Magog and the End of History. There are trees that need planting. There are bomb shelters that need building [and make no mistake, we will need them again one day soon]. There are leaders from every conceivable sector and community of Israeli society who need support. The hungry need feeding. The naked need clothing. The sick need medicine. There are widows, orphans, and refugees in desperate need of our help. We are commanded to do all of these things and more — and do them we must, even if it means that we’ll be long gone by the time the Messiah eventually shows up.

We await God’s anointed every day, even if our righteous actions have the paradoxical effect of pushing him further away.

So come, my friends, we have a Redemption to forestall.

Soli Deo Gloria.

Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 98a.

To those who will find overtly religious framing to be difficult to access or perhaps even repellent, consider what the German philosophers — e.g., Kant, Hegel, or even Marx — call the End of History. We’re all really talking about the same thing: That far-off point in time when humanity has worked out all its issues. That we’ve found a steady state — a civic, social, and political equilibrium capable of sustaining itself in the face of all comers. We are capable of addressing iniquity, we are capable of remediating inequity, and everyone enjoys a peaceful existence.

In other words, if you believe that the moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends towards justice, or you think about a right side of history, or even if you talk about progress… we really aren’t so different.

Even as South Africa dragged Israel before The Hague, it was proudly and brazenly starving to death thousands of penniless migrants, for having committed the grotesque sin of trying to making a living. Turkey, right now, is doing the same thing in Syria.

Perhaps that’s precisely why Judaism deemphasizes eschatology and discourages parlor games about when, where, and how the Messiah is to appear. Our job is not to spend time lost in contemplation about these matters. Because Judaism understands that if we focus on a utopian end-state, it can lead people to do some truly evil and deranged things in order to bring that about. Indeed, the traditional formulation of Jewish messianic belief — as per Maimonides — is: I believe with complete faith in the coming of the Messiah; and even though he may tarry, I shall wait every day for him to come. I find it telling that the operative verb is that we are commanded to wait — and not necessarily to hasten his coming.