Well, there's people and more people

What do they know, know, know?

— John Mellencamp “Pink Houses”

I.

Not long after moving here, I met a friend for coffee to swap stories about our respective experiences of aliyah. Inevitably, this included a discussion of our national obsession with not being a freier. For those unfamiliar with the term, a freier is something you don’t want to be. It is typically translated as “sucker,” but it means so much more than that: The freier is a naïf, a doormat, a rube… someone who is taken advantage of, preyed upon, and passed over by everyone and everything.

And my friend observed (ruefully) an irony at the heart of Israeli freier discourse. He pointed out that many of us are so obsessed with not being freiers at the micro level, yet we’ve managed to overlook that we’re the ultimate freiers at the macro level. Said differently, we are penny wise, pound foolish:

My friend pointed out that Israel consistently ranks among the happiest countries in the world. The methodology turns on asking people to self-evaluate their quality of life against a ten-point scale, with 10 representing the best possible life and 0 representing the worst. Last year, Israel ranked the fifth-happiest country in the world; the year before, Israel ranked fourth. You get the idea.

Against that, Israel consistently ranks among the world’s most expensive countries. And there is also the observable reality that we’re not getting our money’s worth. We pay obscenely high prices for a limited selection of mediocre consumer goods, fork over extortionate amounts of money to live in cities that have subpar municipal services, pay ungodly amounts of taxes to a public sector that’s pretty dysfunctional on its best day. Again, you get the idea.

In short: We’re getting gouged without getting very much to show for it. And yet we seem to think that we’ve got something close to the best possible life.

And so — said my friend — if you described such a situation to the man on the street, wouldn’t he agree that this is the very definition of being a freier?

II.

I’ve thought back to that conversation many times over the last few years, struggling to reconcile the disconnect between our self-reported happiness and the observable reality which we Israelis inhabit.

It could be that we’re all a bunch of freiers. Perhaps that’s because we simply can’t conceive of a better reality — we self-report as happy because we have a limited imagination… we doubt that there’s a world in which things could be any different than they are. We’re doing a fine job meeting or exceeding our very low expectations.

Or perhaps it could be that we’re blissfully ignorant of just how bad things are — we might fail to appreciate the extent to which monopolies, oligarchs, and the like are robbing us blind. There’s certainly evidence to suggest that we do a bad job thinking about the costs we pay. I’ll pick on where I grew up for a moment. It is nice to have cheap consumer goods, access to out-of-season fruit, and the like… but we don’t really do a good job thinking clearly about what we are paying for the privilege. The banana for sale in the supermarket costs a hell of a lot more than what we're paying to take it home. We are paying more for our Amazon Prime same-day deliveries than the membership fees suggest — a price measured in the vitiation of domestic industry, increased carbon emissions, and the like. We don’t think we’re paying anything to Meta or X or TikTok, but our use of those platforms costs us real dollars. We systematically underestimate the price of our decisions — and maybe we Israelis are doing that as well.

In other words, if we dreamed bigger and if we saw reality with open eyes, we surely wouldn’t be as happy as we claim to be. There’s a joke here somewhere, and it’s on us: We might, in fact, be freiers.

But I wonder if there’s a different explanation.

That is, most Israelis are aware of the ways in which Israel is comparatively disadvantaged relative to its peers. There are places that aren’t directly menaced by Palestinian, Iranian, Lebanese, or Yemeni terrorists, which have a steady supply of cheap strawberries year-round, a functional postal service, decent customer service, better communication from your child’s school, and affordable housing.

Our eyes are wide open: We know what it costs us to live here and we know it does not have to be so. And we are all working — individually and collectively — to better our material circumstances. Point in fact, before October 7th and last year’s constitutional crisis, Israel’s last mass civil movement centered on an increase in the price of cottage cheese.

But nonetheless, Israelis are staring at the obscene cost of living here and nonetheless reporting with a straight face that we are happy. And that points to a radical conclusion:

The cost of living here is not equivalent to the value of living here.

Said differently, it’s obvious what this place takes from us and it takes a bit more discernment to understand what we’re getting out of it. And Israelis are saying loud and clear that there is value to this place that isn’t measured in affordable cottage cheese, plentiful housing, a functional government, top-tier public services, or even physical safety. Yeah. We are getting gouged. But even as we grumble about it (and we try our hardest to do something about it), we collectively understand that the price we’re paying doesn’t tell the whole story…

Because we get to live here. We get to live in a place that affirmatively values human attachments and human sentiments — family, faith, community, identity are not liabilities but assets in the context of Israeli society. We get to live fully realized Jewish lives. Our daily lives are informed by Jewish tradition and history and culture. We get agency. Instead of trying vainly to help someone else live up to their ideals, we have a chance to try and live up to ours. We get to live alongside neighbors who would (and often do) put themselves in harm’s way to protect us instead of alongside people who simply giggle and film us while we’re getting sucker-punched (unless they’re the ones doing the punching).

I’ll say it again: The cost of living here is not equivalent to the value of living here. Knowing that and living life accordingly doesn’t make us freiers — it makes us brave.

III.

There’s a lot that economists and investors have to say about cost and value and the relationship between those two concepts (whether there is intrinsic value in a thing; whether there are objective ways to quantify value, etc.). But this much, at least, is clear: Cost and value are neither synonymous nor coextensive.

Pretty much every transaction deals with the tension between these two things. What we are willing to pay for something, what we are willing to give up for something, what we are willing to sacrifice for something … none of these things fully capture what that thing is worth to us. Luxury brands, in particular, understand this point very well, charging large sums of money for something that “objectively” costs very little to make. Chanel No. 5 is made out of water, alcohol, and some flowers. A Louis Vuitton belt is a strip of leather and a metal buckle. And yet, customers are willing to pay a premium that has a tenuous relation, at best, to the cost of the goods.

Value is an extraordinarily hard-to-pin down concept and it certainly relies in large part on intangibles or qualitative metrics. As a result, introducing value into the conversation makes things messy, given that balancing cost and value is often a rather subjective affair. Everyone has a different calculus, and nobody is going to see perfectly eye-to-eye.

It is of course perfectly legitimate to disagree with someone else’s assessment of something’s value. The Talmud, for example, remarks bitterly that the citizens of Beitar went to war with the Roman Empire because someone chopped down a cedar tree and that the citizens of Tur Malka did the same thing over a chicken. It must have been one heck of a tree and it must have been an extraordinarily special chicken.

But even so, this much is clear: Value matters. And we get ourselves into trouble if we focus solely on what someone is paying for a thing without considering what that thing is worth to them, and how they value it.

And when we look beyond cost and start to consider value through a lens of empathy and curiosity, we instantly liberate ourselves from freier discourse.

In other words, the accusation of freier says a lot more about the speaker than the recipient. If we call someone a freier, we’re simply admitting that we don’t appreciate the value that they’re getting in exchange for the cost they’re paying. The client with the winning case but prefers to settle it. The drivers who yield despite having the right-of-way. The person who gives up a seat on the bus so someone else can have it. The parents who are willing to commute daily to send their kids to a certain school, even though there are other options closer to home. Maybe they’re all freiers. Or maybe they just value something that’s not readily apparent to us.

I think about the people who roll their eyes and chuckle at the tradeoffs I make as I go about my daily life. If I’m being charitable, perhaps they’re calling me a freier because they assume I don’t know any better, and that’s their misguided attempt to try and educate me (“but you could get there faster if you didn’t yield!”). But really, I think they’re telling on themselves: They’re admitting that they don’t see what I see. They’re admitting that they’re seeing only the cost I’m paying and can’t see or appreciate the value I’m getting.

But if they operated instead from the premise that my eyes are wide open, things start to look awfully different: I know exactly what it’s costing me and I still choose to do it anyways.

The same holds true at the collective level. Israelis know what it costs us to live here. But we make our choices with open eyes and an open heart. This does not make us suckers. It makes us human beings — principled ones… empowered ones! — and the only freiers are those who condescendingly sneer and are foolish enough to bet against us.

IV.

If we know that Israel has an intolerably high cost of living, but that the cost of living isn’t coextensive with the value of living here — what strategy sits downstream from these insights? In other words, what are we supposed to do about all this?

I have to start by emphasizing a critical point: The fact that the cost of living here doesn’t fully capture the value of living here does not — repeat, does not — mean that the cost of living is irrelevant. It matters, deeply, whether or not a person can go to sleep with a full stomach, that they are able to afford healthy and nutritious food, that they have access to affordable and high-quality medical care. And the fact remains that our exorbitant cost of living does not translate into a sufficiently high or equitable standard of living. This is unacceptable.

There are a handful of extraordinary platforms and changemakers who are working hard to combat food insecurity, to broaden access to shelter, to strengthen the healthcare system, and to improves the socioeconomic standing of marginalized and peripheral communities in Israel.

But I am clear-eyed about the limitations of this strategy. For starters, there’s only so much that civil society can do here. Cost of living sits downstream of a patchwork of laws, regulations, and market forces — and radical change will only occur if there are intentional political reforms in tandem with disruptive private sector innovation. Business and government are much better positioned than the world of philanthropy and social impact, at least when it comes to fixing the cost of living. And more to the point, a monomaniacal focus on the cost of living and improving the standard of living — to the exclusion of everything else — leads inexorably to a dystopia worthy Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. If this is all that we’re doing, it culminates with the vast majority of humanity subsisting on universal basic income, pantries stocked grace of same-day delivery, and our minds kept satisfied infinite of content grace of Netflix, et al. Some might call that satisfactory — but the data suggest that most Israelis disagree. Cheap consumer goods at the expense of human dignity and purpose? No thanks. Affordable housing in a way that hollows out community and rootedness? Hell no. We are saying loud and clear that the cost of living here and our standard of living matter — but they aren’t the whole story: They don’t fully capture the value of living.

A future powered by Amazon and AI would boast a higher standard of living alongside a lower cost of living. Those are good outcomes. Period. But if we allow cost to totally eclipse value, the experience of living would be greatly diminished. And so we must insist on there also being a robust infrastructure of value — the kind of stuff that helps cultivate family, belonging, identity, faith, and rootedness… the hard-to-quantify things that are truly essential to human flourishing and happiness.1

And here, the world of social impact has a lot to offer. The Fourth Quarter, for example, is a radical and innovative platform that’s working to get Israelis to meaningfully engage with one another — to ask each other hard questions, to listen and learn from peers with radically different perspectives, and to think together about building a shared future in a polarized country. There are other platforms that are centered on civic activation — getting people off the couches and into the streets and fields to volunteer, pay it forward, and help one another. There are remarkable nonprofits that are likewise asking hard questions about what Judaism and Jewishness means in this day and age — and turning those insights into action.

They are working to both cultivate and leverage those invaluable things not captured by the cost of living — our sense of mutual responsibility towards one another, our identities, our desire for agency. If we can do that successfully, then I’m hopeful that even with all that we’re experiencing and going through, that we Israelis will continue to report high levels of happiness.

V.

I return — again and again — to the question that the rabbis pose to prospective converts. To offer a rough paraphrase, the Talmud instructs the rabbis to ask those seeking to join the Jewish community: “What have you seen that makes you want to convert? Aren’t you aware of how difficult it is to be Jewish nowadays — how much they hate us, and how dangerous it can be to be part of this people?”

And the right answer (i.e., “I know what I’m getting myself into, but I want to do it anyways”) is one that evidences awareness of the considerable costs of being Jewish, while also expressing a keen sense of value.

I’m looking out at the Jerusalem skyline as I write this, watching the sun reflect off the light pink stones.

Two-and-a-half millennia ago, the armies of Babylon ringed these hills, besieging the holy city. Jerusalem was doomed; the city’s fate was sealed. And the prophet Jeremiah had been thrown in the dungeon for having dared to say so. But at that very moment, God delivers a message to Jeremiah:

“Buy land.”

If the goal is to make a quick buck, the command is hard to understand. This is arguably the world’s most baffling instance of insider trading: The financial value of the investment is about to get obliterated (and Jeremiah knows it). It will be generations before it recovers its value.

And so, Jeremiah objects (politely), questioning the wisdom of essentially lighting his money on fire.

And in response, God validates — explicitly — Jeremiah’s concerns. God recounts the tragic history of how the people of Israel went astray, polluting the land and disobeying the Torah. And God reiterates that Jerusalem will be destroyed and its inhabitants exiled. But then, says God, they’re coming back. God promises that one day, the Jewish people will return to this land:

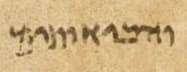

And the field will be purchased in this land of which you say: “It is a wasteland, devoid of humans and beasts — delivered into the hands of the Chaldeans.”

Fields will be acquired for silver, and deeds recorded in books, and witnesses assembled — in the land of Benjamin and in the environs of Jerusalem, and in the cities of the foothills, and in the cities of the coastal plain and in the cities of the Negev — for I will bring back their captives: This is the word of God!2

This story is in so many ways a perfect metaphor for what it means to be part of the Jewish people, or to be part of the State of Israel, or to be part of any community anywhere — religious or secular, Jewish or gentile — that is forged in values and that comes together, united in purpose:

Do things that makes no sense on the surface. Make decisions that seem incomprehensible to others. Give a lot to get back what others might think is very little in return. Make investments that are unlikely to offer a return in your lifetime. If they want to call you a freier, wear it as a badge of honor. And then go back and do it all again. And again. And again.

Do it smiling all the while — even as they roll their eyes at you, whisper behind your back, protest you, boycott you, and try to shut you down — because the joke’s not on you. Because you know the value of your time, your money, your blood, your sweat, and your tears.

Because you’re building a future.

I have tried to make an analogous point as relates to safety and antisemitism. We shouldn’t court danger — and we shouldn’t despair of self-protection. But I believe that investing in Jewish identity is a far better long-term strategy for Jewish life than anti-antisemitism. The same holds true here: We can and must work to improve the standard of living and lower the cost of living — and (not but) we cannot for an instant lose focus as relates to our values.

Jeremiah 32: 43-44.

I love the observation that this mentality leads to 'penny smart, pound foolish' decision making. It is at the root of our unwillingness as a nation to accept short-term losses for long-term gains, one of the hallmarks of maturity. Well written and argued.