I.

The Talmud tells of the events culminating in the destruction of Jerusalem and the forcible exile of the Jewish people from their historic homeland: A dinner party goes horribly awry and a jilted guest embarks on a convoluted revenge plot, successfully convincing the Romans to destroy what’s left of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel. Emperor Nero himself travels to the Holy Land to personally lead the war effort. Upon arriving, a series of miraculous signs demonstrate to him that God’s wrath is indeed directed towards Jerusalem: Nero fires arrows in each of the cardinal directions, yet they all bend back towards the holy citadel.

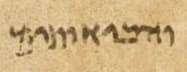

Then, for reasons unexplained, Nero takes it upon himself to interrogate the nearest Judean schoolchild and asks him to share the Biblical verse that he learned that day. The child cites Ezekiel 25:14,1 a verse that puts the fear of God (literally) into Nero’s heart. Nero concludes that it evinces God’s intent to use Rome as an agent of retribution against the Jewish people, but to then punish Rome for having hurt the Jews.

… And so (says the Talmud) Nero runs away, converts to Judaism, and his eventual descendants became great Torah scholars.

I read this narrative as a young kid – a small part of a larger text that I took (and still take) both seriously and literally. And it prompted something of a crisis in me. I had read every age-appropriate text on the Julio-Claudian dynasty and the early Roman Empire that I could get my hands on. And I knew that what the Talmud said could not easily be reconciled with the history books. There’s no record of Nero having traveled to Judea. And Nero probably wouldn’t have been capable of highly sophisticated Biblical exegesis. And Nero probably didn’t retire from public life and become a convert: He was deposed in a coup d’etat and was mercy-killed by his retinue before he could fall into the mutineers’ hands.

This wasn’t the first time that I had encountered a religious text that was difficult to reconcile with science, or history, or my conventionally American way of life. But for reasons I can’t even begin to explain, this one really knocked me sideways.

I uncharacteristically kept this one very close to my chest. I spent years with this bottled up inside of me. I let it ferment. I was terrified to voice my doubts and concerns. Would they kick me out? Would there be a place for me in this community? Would God reject me? All the while, I felt myself decaying from within — my mind punishing itself for its own thought-crimes — even as I tried to convince myself that maybe somehow the Roman sources got it wrong and that Nero did live out his days playing the lyre somewhere in the Galilee.

Until one day, in a moment of impulsive vulnerability, I unburdened myself to my tenth-grade Talmud teacher. He was a man with a towering intellect and with an extraordinarily good heart. He ministered to the misfits. He wasn’t afraid to ask provocative questions. He wasn’t afraid of the haters. I must have known on some subconscious level that he would treat me with magnanimity. And so I unspooled the whole story to him: Here is what the Talmud says, here is what the historians say, and how on earth am I supposed to function, and what I am supposed to do with a sacred text that simply doesn’t jive with what we Know To Be True™?!

My teacher fixed me with a steely look and responded, not unkindly, but with an unexpected edge to his words and tone:

The Talmud isn’t meant to be a work of history. The rabbis are trying to teach you something else.

… I think on some level, I had been hoping that he would say: Tacitus is right. The Talmud is wrong. But here’s what you’re supposed to do about it. Thankfully, no such luck. Because that would have been the easy way out, and my teacher — a man of blessed memory, departed far too soon — was teaching me something far more profound.

He helped me begin to understand that there is such thing as historical truth and there is such thing as Talmudic truth. Sometimes, the two happen to overlap, but that won’t always be the case. And the friction between them does not undermine their respective integrities, for each of these things aims at a different goal and is therefore fit for a different purpose. My teacher helped me understand that (to paraphrase Rabbi Jonathan Sacks) there is one God — and that human existence, human knowledge, and human experience are characterized by pluralities. And that cognitive dissonance therefore is not a bug, but a feature of life itself — a feature that might at times feel burdensome and oppressive, but that actually is an extraordinary gift and blessing that God has given us.

II.

I operate from the premise that every single human system is limited in its ability to contribute towards human flourishing, to explain the universe, and so on. And that being so, it follows that we need to reconsider how different systems and different disciplines relate towards one another.

Consider, for example, Michelangelo’s Last Judgment:

As a work of art, it’s without parallel. But from a medical perspective, it leaves a ton to be desired. While Michelangelo’s figures are imbued with a verisimilitude of sorts, when you actually look at the work up close, you can see that he portrays the human anatomy in strange, exaggerated, and extreme ways. Michelangelo flat-out invents random muscles, and depicts limbs, sinews, tendons, and muscles interacting in ways that are physically impossible:

Conversely, while a medical textbook may offer a helpful set of diagrams showing how muscles are supposed to look and function, but you’d be hard-pressed to call any of that art. Those drawings aren’t exactly going to produce a powerful aesthetic experience, move people to tears, or prompt them to conclude that they must change their lives.

Which is to say, it would be missing the point entirely to try and judge a work of art in medical terms, just as it would be silly to judge medical diagrams in artistic terms. Or to badmouth a classical pianist for his lack of prowess at jazz flute. What makes a good candidate for office does not necessarily make a good officeholder. When you’re sick, you go to a medical doctor; when you’re on trial, you seek out a juris doctor.

In other words, we understand intuitively that the world is composed of many different systems. Each one aims at advancing a different set of goals and each one aims at solving a different set of problems. Each and every system has its own internal logic, its own internal language, and its own set of internal criteria for excellence and merit. Each and every system has to be judged on its own terms.

And perhaps most importantly, each of these many systems is limited: There are some problems that a system can address, and there are ones which sit outside of its scope.

… And that’s just fine!

The fact that mechanical physics can’t explain certain phenomena occurring at the subatomic level doesn’t mean mechanical physics as a discipline is wrong; it just means that it is limited. Thankfully, we also have quantum physics — it complements the gaps in our understanding that are beyond the explanatory powers of mechanical physics. The fact that there are questions that the law can’t answer doesn’t mean that there is something wrong with the law… it’s just limited.2

All systems are limited. Every system is incomplete.

… And that’s totally fine.

III.

That said, there is a hidden danger to this. Because awareness of limitations (whether in oneself or in others) can lend itself to an unkind ethos of shut up and dribble. I’m certainly not arguing that everything and everyone should stay in their own lane. To the contrary, we would lose something invaluable if that happened. We need to be curious about what’s happening outside of our cubicles, and we need to be courageous enough to consider what we owe to our neighbors. Because extraordinary and wonderful things can come from cross-pollination, interdisciplinary thinking, and multi-sectoral interventions:

Apply the scientific method to interpersonal relationships. Use speculative fiction to think about public policy. It turns out that baseball has a lot to say about religion (and vice versa). Celebrities can and should use their platforms to catalyze social change. Publicly traded companies can do an awful lot to combat climate change or promote national service.

Good things happen when limited systems interact with other limited systems — because together they are capable, as it turns out, of building something that is greater than the sum of its parts.

But for this to work, what’s needed always is an awareness of the relevant systems and actors’ respective limitations. When you’re asking an economist to comment on molecular biology, adjust your expectations accordingly. If poets feel compelled to opine on fiscal policy, they certainly should not bite their tongues — but they should just consider the strengths and limitations of what they bring to the table. Again, every system is differently limited and differently suited for purpose. And as long as we are aware of those limitations (and strengths), then we should encourage as much partnership, dialogue, and interaction as possible.

In present terms, this insight is precisely what sits at the heart of our most consequential bet in terms of social impact. We’ve helped build a diverse and pluralistic network of over a thousand leaders from all walks of life here in Israel — a network that’s rooted in the recognition that no one community, no one sector, no one system has the Answer… and it’s only through meaningful and mutual engagement with others that we can hope to get somewhere.

IV.

With this in mind, I’d like to apply the lesson of Nero’s Arrows to a system where the stakes feel a bit higher: Liberalism.

Just like copyright law, mechanical physics, Judaism, or medical science, liberalism is a system that aims at specific goals and is fit for specific and discrete purposes. It provides answers – and excellent ones, at that! – for the questions it was designed to answer. If you’re seeking to safeguard individual liberty, increase prosperity, and promote political stability — you’ll be hard-pressed to find a better system than liberalism. But like all systems, liberalism has meaningful and profound limitations and it isn’t remotely equipped to handle things outside of its purview. In other words, there are problems to which liberals, liberalism, and liberal institutions cannot supply an answer.

And yet too many of us are expecting far too much from liberalism. Call it liberal determinism, call it liberal monism, call it liberal imperialism – call it whatever you want… the problem is one of hubris and overreach. Because liberalism isn’t a panacea: It is a bounded system and we’re setting ourselves up for trouble whenever we allow ourselves to think otherwise.

For starters, when we ask too much of liberalism, not only do we end up hurting ourselves… we also end up profoundly disillusioned with liberalism. That is, liberalism is spectacularly ill-equipped to handle our basic and affirmative needs for attachment and passion. As a system, liberalism has always been suspicious (at best) or antagonistic (at worst) towards things like Identity, Family, Tribe, or Religion. For centuries, it has tried to chase these things from the public sphere… to banish the chaotic, the messy, the unpredictable, the all-too-human, from the realm of governance and politics.

On the one hand, we ought to be thankful that liberalism has been as successful as it has been in reducing the harmful effects of these things. People enjoy more peace, more prosperity, and better quality of life precisely because we have worked to limit the effects of passion and attachment in politics. Accidents of birth are less likely to get people killed than at any other time in human history. These are extraordinary and wonderful accomplishments, period, full stop.

But here’s where it gets tricky. We are social animals and hot-blooded creatures. Attachment and passion are part and parcel of who we are; they play affirmatively valuable roles in our lives. We need Identity. We need Belonging. And so on. And it’s therefore insane to expect that a system — viz., liberalism — which is hostile to those things can satisfy our need for those selfsame things. We cannot expect liberal institutions (e.g., political parties) to speak to the profoundest mysteries of human existence, or our deep needs for community, identity, and belonging. And yet, that is precisely what we’re doing.

We can’t be mad at a spoon for not being a knife. We shouldn’t fault the Talmud for failing to be a history book. And we shouldn’t fault a painting for being a poor guide to the human anatomy. But that’s exactly what we’re doing with respect to liberalism. We outsource to liberalism and liberal institutions tasks more properly directed to priests, rabbis, psychologists, family members, and our community members… and when we inevitably find ourselves Bowling Alone, we have the temerity to claim that liberalism failed us.

***

There’s another danger when we ask too much of liberalism — namely, that we miss out on the richness of human existence itself. Take, for example, the tired and tiresome discourse about the relationship between Zionism and liberalism. There is a never-ending cavalcade of New York Times think pieces on the subject. And if you’ve read one, you’ve read them all: The author portentously highlights tensions (real or imagined) between Zionism and liberalism, then concludes by importuning American Jews to choose between the two systems once and for all (or else…).

Such pieces used to make me angry. Now I mostly just feel sorry for the authors. Because let’s assume for the sake of argument that everything they’re saying is right – that Zionism and liberalism can’t easily be reconciled, perhaps even at all.

So what?

Science and religion do not easily coexist. And yet there is room in my life for both rabbis and doctors. I know when to call one and when to call the other. Likewise, I can read the Talmud and a history book, and I can appreciate each one of these on its own terms even when they contradict one another. And in the same fashion, I insist on my right to be a liberal — and to complement that liberalism with other -isms, other disciplines, and other ways of experiencing the world. I draw on my liberalism when the situation calls for it. I draw on other systems and institutions when those are needed.3

And so whenever someone insists that I need to pick between two modalities of human existence, belief, or knowledge, I pity them. The need to shoehorn everything into a single mental and moral matrix reveals a sad, shallow, small-mindedness. The insistence on discarding whatever doesn’t fit reveals fear, dressed up in arrogance.

To go through life without cognitive dissonance is to exist without really living. It’s to miss out on the incredible and sometimes terrible beauty that this world has to offer. And cognitive dissonance isn’t possible as long as we allow monisms and deterministic theories to crowd out all conceivable alternatives.

***

If we want liberalism to flourish, we need to be mindful of what we’re asking it to do. If we want to be fully realized human beings, we need to stop searching our source for some definitive human system.

But please don’t misunderstand. This isn’t about liberalism, per se. Or art history. Or Judaism. Or any given discipline or system. Really, all I’m doing is arguing broadly against a worldview of determinism, against an existence characterized by overreach, imperialism, and ideological conquest. I’m arguing for a worldview of complementarity and ecumenicalism – a way of living in which a plurality of bounded and limited human disciplines all exist alongside one another, each contributing what it can towards human flourishing, each supplying answers to the questions it is able to answer.

V.

I began with a story about the Destruction of the Temple. I’ll close with a story about Creation.

There is a tradition within Judaism that God’s creation of the universe began when He figuratively contracted Himself to make room for Creation. Tzimtzum — i.e., self-contraction — in other words, is the building block upon which our collective existence is predicated.

It’s easier to understand what tzimtzum might look like through considering it in the context of a parent’s relationship with a small child. In the eyes of the child, the parent is effectively omniscient and omnipotent. And thus the child has no hope whatsoever of growth, of spreading their wings, and of becoming their fully realized self unless the parent gives the child space to do so. And we see what that looks like when kind and thoughtful parents, if asked a question to which they already know the answer, summon the patience to smile and respond: “well, what do you think?”

Self-contraction can be difficult. But it is necessary in relation to Other, and it is a redemptive and cathartic experience in terms of Self. Indeed, there is profound beauty that comes from doing so. To be given space to breathe, to mess up, to learn, to try, to grow, and – yes – to build. And to give others space to do the same.

And that is the point:

The economists write about creative destruction — dismantling and disrupting as a precondition for innovation. By contrast, Judaism suggests that self-limitation (or recognition of limitation) is what enables us to collectively transcend those selfsame limits — and build something better, together.

When systems overextend themselves — when we look to liberalism to supply us with Meaning and Identity, when we look to the Talmud to teach us Roman history, or to Michelangelo to understand the human form — that’s when we get ourselves in massive trouble. Not only do we set those systems up for failure, but it is suffocating, constraining, and disabling for us. Totalities and determinism leave no opportunity to grow, to experiment, to learn, to do anything.

Thankfully, we are instead called to emulate our Creator and engage in tzimtzum. And indeed, when there is self-contraction, when the flood waters recede, when things are restored to their proper place, cognizant of what they are and what they are not… the vast space left behind gives space for extraordinary things to happen.

“And I shall inflict My vengeance upon Edom, through the hands of My nation Israel…” [translation is my own]

Even my religion — Judaism — is by its own terms a limited system. This isn’t a particularly novel or earth-shattering claim. Judaism, as a system, never makes claims on universality. For example, Jewish text makes it explicit that personal salvation or a share in the World to Come do not depend on being Jewish. While there is a common denominator of universal morality (e.g., don’t steal, do justice, don’t murder), Judaism categorically does not expect or require or encourage non-Jewish people to keep kosher, circumcise their sons, or observe the Sabbath. Judaism supplies a particular set of answers directed towards a particular set of questions, and for a particular set of people.

And to be clear, this doesn’t make me post-liberal, illiberal, a bad liberal, or anything of the sort. If anything, the critique works the other way around: If you’re asking your lawyer to pick up your laundry, that makes you a bad client. And I’m a better liberal precisely because I do not expect liberalism to do it all. I try to be aware of liberalism’s limitations and I try to calibrate accordingly. There are questions to which liberalism cannot supply an answer… and we do a disservice to liberalism to ignore its limitations.