The Grove

"And I looked up through a pain so intense now that the air seemed to roar with the clanging of metal, hearing, HOW DOES IT FEEL TO BE FREE OF ILLUSION . . ."

In the spring and summer of 1944, the European genocide of the Jewish people reached its satanic apogee. The lessons that the Nazis and their collaborators had learned over the previous decade were deployed with terrifying exactitude and efficiency to destroy and dismantle the Jewish community of Hungary — murdering more than half a million men, women, and children in a matter of weeks.

Like those who filmed themselves raping, torturing, kidnapping, and murdering the residents of southern Israel, the Nazis also made obscene and barbarous records of their crimes. Among the most disturbing of these is the so-called Auschwitz Album. The album is a collection of photographs showing the arrival of Hungarian Jews at the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp. And while it does not depict any dead bodies or the act of killing — it shows my people in the final moments before their murder (if you wish to see it, you can do so here).

It begins with photographs of Jews lining up, awaiting “selection” — an obscene euphemism to describe the process whereby doctors… men who had sworn the Hippocratic Oath!… would determine which Jews would be murdered in gas chambers (if not burned alive), and which ones would be worked to death as slaves. It continues to show photographs of Jewish mothers carrying their babies, grandmothers and grandfathers, little boys and girls walking hand-in-hand… all being herded towards the gas chambers.

It is unbearable to look at. Every single person depicted therein was cruelly and barbarically murdered just minutes after these photographs were taken, their bodies burned and dumped into the fields. Brothers and sisters. Mothers. Grandparents. Babies. Entire worlds, destroyed.

But perhaps the most horrifying photographs of the album show women and children assembled in a small grove of birch trees just outside of the gas chamber — waiting to be murdered. Devoid of context, it almost seems idyllic; if you could somehow ignore the yellow stars sewn onto the children’s shirts, you might even allow yourself to imagine it shows a picnic or a family outing.

We know what happens next.

But first, look carefully: And there, frozen in time, is a little boy — a toddler — picking a flower and showing it to his older brother.

***

Many years before these photographs were taken, another group of Jews assembled in a grove, albeit for very different purposes. Tradition speaks of four sages — Rabbi Akiva, Acher, Ben Azzai, and Ben Zoma — who entered into an orchard. They were beset there by tragedies of a fundamentally different sort: Ben Azzai died. Ben Zoma went insane. Acher lost his faith and became a heretic. Only Rabbi Akiva emerged unscathed.1

This is the story of the Pardes — the story of the Four who entered the Grove. The standard interpretation invokes the supernatural: These scholars — leaders of their generation — attained mystical insight and/or gained access to some higher plane of reality. And the overwhelming majority of the group was unable to handle what they encountered: One lost his body; one lost his mind; one lost his soul.

I don’t quarrel with that interpretation in any way, but I don’t think one needs to resort to mysticism or the metaphysical to explain the story.

Because all it takes to undo a person is to see the world as it really is. To see humanity and all of creation in the plain light of day.

This might not sound especially painful — but it is. Stripping away illusion is enough to break the strongest bodies, the soundest minds, and the purest souls. It is an act of violence. How exactly does it feel to see that your underlying assumptions about how the world worked were dead wrong? That the institutions which cashed your checks were only too happy to turn on you? That the professor who wrote your letter of recommendation believes rape and infanticide are acceptable forms of “resistance” so long as they’re directed against your people? That people who danced at your wedding don’t give a damn if you or your children live or die? That Batman isn’t real but that monsters actually exist?

Pardes doesn’t need to be the Garden of Eden.

It is a small copse of trees in southern Poland. It is an orchard in southwestern Israel.

Pardes is here. Pardes is now. You’ve seen it. You’re living in it.

***

Southern Israel is the closest thing to a terrestrial paradise I’ve ever experienced. The natural beauty of the region is incomparable. Walk through the fields where Nova took place, or drive down the boulevards of Sderot, or walk through the gardens of Kfar Azza — if you could forget for a moment what transpired there not so long ago, it might even feel edenic.

The flowers are blooming right now — red anemones are blossoming throughout the area — and we are hard at work rebuilding.

But step into the groves of southern Israel and see the world as it is: The trees that line the highway bear witness to savagery. You can see the bullet holes and the burn marks. This is where Hamas and its supporters came to rape, to kidnap, to torture, to brutalize, to murder. And that is what they did. They even stole innocent civilians — including dozens of little children — from their bedrooms and nurseries.

… All of the children are home now. That isn’t to say that any of them came back intact or healthy. But — until recently — they all came home alive.

… For five hundred days, one of the few stories that Hamas’s defenders have been unable to whitewash and one of the few stories has somewhat broken through the tide of pro-Hamas propaganda (forget Al Jazeera for a moment and consider the depraved insanity that comes from the BBC) is the story of the Bibas family.

You know by now the names of Kfir and Ariel Bibas. You’ve probably also seen their faces. Kfir was nine months old. Ariel was four. They were stolen on October 7th — a savage mob kidnapped them and dragged them and their mother Shiri across the border to Gaza. You have probably seen the footage — Shiri, terrified; the baby brothers wrapped tightly in her arms as they suck on their pacifiers.

And you know by now that these babies were cruelly tortured and held in inhumane conditions. And you know by now that in the first weeks of the war, their captors murdered these two little boys and their mother in cold blood.

And you know by now that in order to bring these murdered babies back to the orchards of southern Israel, Israel was compelled to release hundreds of Palestinian prisoners — hardened and unrepentant terrorists with the blood of innocents on their hands.

… Do you see the world as it is? Did you see Hamas parading the coffins of these babies on a Gazan soundstage — as music blared and a crowd of men, women, and children cheered lustily? Did you see that Hamas sent Israel the body of an anonymous Gazan woman — attempting to pass it off as Shiri’s? Did you know that Hamas stuffed the children’s coffins full of terrorist propaganda?

Have you seen the videos of Ariel Bibas — dressed like the Batman who never came to save him — running, giggling through the groves of southern Israel? The photos of him cuddling with his mother and his baby brother in a sunny glade — are they seared in your mind like the image of the little boy handing a flower to his brother in the shadow of a gas chamber?

… The Nazis burned that little boy. And last week, our people buried Ariel, Kfir, and Shiri in a single casket.

***

In recent days, we have all gained access to pardes. We are being shown the world as it is — a place where Jewish toddlers and babies are stolen from their cribs, tortured, and murdered savagely… a world in which we are forced to release the murderers of other Jewish babies for the privilege of burying the desecrated corpses of these ones.

Stand in this grove, look around and see that it has always been this way:

Elad and Hadas Fogel were the same age as Ariel and Kfir Bibas when two Palestinian terrorists murdered them one Friday night. They were murdered with knives and with bare hands — alongside their eleven-year-old brother and their mother and father. Shalhevet Pass was also ten months old when she was murdered by a Palestinian sniper as she lay in her baby carriage. Einat Haran was four years old when a Lebanese terrorist beat her to death (and only after first shooting and drowning her father, before her very eyes). Before them, there were Jewish toddlers who were picking flowers in a grove one moment, and then stripped naked and forced to inhale hydrogen cyanide in the next.

That is the world as it has always existed.

We’re told by best-selling authors, elected officials, and keyboard warriors that it’s gauche or morally reprehensible to talk about Jewish victimhood or to take a lachrymose conception of Jewish history. These are, of course, the same ghouls who only permit us to mourn our dead if we deracinate them … if we erase that which makes our dead dear to us. To them, Jewish grief is only acceptable if the victims are universalized… if we are made to mourn the suffering of others in the same breath. “The problem, you see, isn’t the murdered Jews — it’s the Jewish grief!”

I refuse to play their obscene games. And I likewise have no time for those who are so lost to this world as to confuse rock with water, murder with death, or good with evil.

No. I confront the world as it actually exists: A place where Jews sometimes triumph over adversity against all odds and a place where Jewish children are murdered notwithstanding whatever agency and resources we have at our disposal.

So no. This is not a cry of helplessness or an invitation to passivity. We must confront evil; we must make it harder for bad people to hurt good people. And I will do everything in my power to ensure that my children and yours inherit a world that is materially better than this one. But that starts with clarity and understanding: That for now, this is the water in which we swim and in which we have always swum; that my children are not safe and neither are yours.

To see this truth — and to live in this truth — is to risk your body, your mind, your soul.

But God help us, we cannot live by lies.

***

It is blasphemous — now more than ever — to speak of silver linings. There are no silver linings to pain and evil such as this. It likewise feels obscene to speak about closure, of healing, of comfort. Certainly not when our comforter eludes us and is driven ever further away. No — instead we are surrounded by thorn bushes and jagged truths that leave us bloodied and torn up every time we dare to approach them.

That is the grove. That is history. That is life.

Only one in five Jews left Egypt to try and live in this brave new world. Only one in four of those who gained access to truth proved capable of living in it.

In times such as these, it’s easy to see why.

So what was Rabbi Akiva’s secret? How did he manage to be the minority of the minority? How did he manage to live in truth without completely losing his sanity or without most respectfully returning his ticket?2

In my darker and more cynical moments, I fear that Rabbi Akiva had innate talents with which the rest of us haven’t been graced. He was, after all, the man who looked at the smoldering ruins of Jerusalem and burst into laughter — not because he was delusional or failed to grasp the horrors before his eyes, but because he could sense what was to come.3

Maybe he was just born that way and there’s no hope for the rest of us.

But a dear friend and teacher helped me understand that the key to Rabbi Akiva’s ability to leave the grove in peace was his commitment to a Torah of lovingkindness. As my friend explains, Rabbi Akiva took the Biblical imperative to love your neighbor as yourself4 as a tentpole of his entire worldview: Love was the ethos which suffused his entire life — and it was front-of-mind for him even at his moment of death.5 Love sustained him in the face of personal hardships, professional challenges, national catastrophes, and unbearable truths. Love gave him what he needed to keep on going.

Again, you could try to argue that Rabbi Akiva simply had a preternatural ability to love. That he was just simply hardwired for this. That it comes more easily to some rather than others.

But love is a muscle and a capacity that can be cultivated.

And in this sense, I presume to cite the Torah of the very first rabbi I had the privilege to know. He was a remarkable figure of blessed memory… a man who was a worthy heir to Rabbi Akiva… a man whose considerable intellectual firepower was equalled only by his towering emotional intelligence and his abundant lovingkindness.

Someone once asked him in a quiet moment how we’re supposed to love our neighbors when those selfsame neighbors often prove to be so very aggravating. Patiently and kindly, the rabbi responded with a question of his own: How do you get to Carnegie Hall?

He paused for effect and cracked a wan smile:

Practice. Practice. Practice.

***

The only way to live in this world — the only way to live with unbearable truth — is to try. With all your heart. With all your soul. With all your might. Sustained by love of others. Sustaining others with your love.

Take that love and put it to good purpose: Confront evil. Do justice. Act righteously. Just try.

Practice. Practice. Practice

Maybe one day — when the grass has long since grown through our cheekbones — our children’s children will merit to reap different fruits than the ones currently at hand.

For now, we’ll be toiling here in the grove with open eyes and broken hearts.

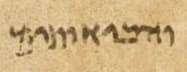

The story is told in several texts. The version as it appears in the Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Chagigah 14b reads as follows [translation is mine]:

Four entered into the orchard — Ben Azzai, and Ben Zoma, and Acher, and Rabbi Akiva. Rabbi Akiva said to them: When you stand opposite stones of pure marble, do not say “these are water” — as it is written: “One who utters falsehood shall not be established in My sight.”

Ben Azzai glimpsed and was killed. Regarding him, Scripture says: “Grievous in the Eyes of Hashem is the death of His righteous ones.”

Ben Zoma glimpsed and was stricken. Regarding him, Scripture says: “You have found honey; eat enough, lest you become sated and vomit it out.”

Acher mutilated the saplings.

Rabbi Akiva left in peace.

To be clear, if we look closely at the text of the Pardes story, the Talmud suggests that even Rabbi Akiva didn’t actually make it out of the grove unscathed. That is, the Talmud states that Rabbi Akiva exited the pardes “b’shalom” — meaning he left the orchard “in peace.”

Among traditional Jews, that is very charged language. That is, when you take leave of someone, you tell them "go towards peace” — and when you say goodbye to a dead person that you them “go in peace”. See Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Berachot 64a. The idea being that there is no closure or finality for the living; only the dead are truly at peace.

And so, when the Talmud tells us that Rabbi Akiva left “in peace,” it effectively paints him as a dead man walking, perhaps foreshadowing his eventual martyrdom. He has his sanity, his soul, and his health (for now) … but the text gives us the sense that his days are numbered.

See Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Makkot 24b.

Leviticus 19:18.

That is, as he was being tortured to death by the Romans, even then, Rabbi Akiva’s thoughts turned towards love. With his dying breaths, he meditated on the commandment to love Hashem, your God, with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your might (Deut. 6:5). See Bablyonian Talmud, Tractate Berachot 61.