I.

We’ve heard the story before: The Jewish people were camped at the border of Canaan. They were on the cusp of reaching their destination. And then they absolutely blew it. They sent twelve leaders — the Spies — to scout out the land. And when the Spies returned, they incited a panic, exacerbating the people’s doubts about the wisdom of entering into the Promised Land. The people rebelled and took steps to return to Egypt. In response, God condemned the nation to wander the desert until every single adult man died out.

Only two men were spared this fate:

The first was Caleb — son of Jephuneh. Caleb was one of the Spies, but he very quickly distinguished himself from the pack. If the other Spies were characterized by a realism that lapsed into a cold cynicism, Caleb was driven by profound and intense faith: He saw value where others perceived only cost. Caleb had broken ranks with the Spies from the get-go: He consistently and publicly registered his disagreement with the Spies’ assessment of the Land — doing so before the rest of the group had hardly finished delivering their report.

The other? Joshua — son of Nun. Joshua was also one of twelve who scouted out the Land. Like Caleb, Joshua ended up disagreeing publicly with the Spies and attempted to quell the rebellion. But unlike Caleb, Joshua was not an early and enthusiastic dissenter; he broke with the Spies only once the people started mutinying — i.e., towards the very end of the tragic affair.1

***

Now fast-forward thirty-eight years:

The rebellious generation has completely died out. The Jews are once again on the banks of the Promised Land, Moses is about to die and someone else needs to lead the nation into Canaan. In the wake of our national catastrophe, given the choice between Caleb and Joshua, whom would you rather choose: The one who was right from the get-go… or the other guy?

Spoiler alert: God picks Joshua, not Caleb.

Caleb certainly gets his due; he’s singled out for praise and is richly rewarded when the Jews eventually enter the Promised Land. But Joshua is the one who is chosen to to bring the people into the Land… the land that Caleb defended. Joshua gets to the lead the conquest of the Land… the task that Caleb insisted was possible.

By contemporary standards, this does not make a great deal of sense: Society tends to elevate those who were “right” from the get-go, while punishing those whose views evolved. Nowadays, the voting public tends to reward leaders who know how to make a good and prescient speech. Point in fact: The 2008 U.S. Presidential election was essentially a choice between two would-be Calebs.2

Yet by anointing Joshua as Moses’s successor, Jewish tradition invites us to reconsider the wisdom of our present-day approach. Yes, Caleb is worthy of our praise and admiration; yes, prescience and consistency are virtues. But the Torah wants us to understand that Joshua’s conduct during the story of the Spies shows why he — not Caleb — was the right man to the lead the people into the Promised Land. Because what distinguishes Joshua is that he was the sort of leader who worked to effect change through coalition — working from within and even behind closed doors.

Here goes:

II.

As we’ve seen, Jewish tradition views Caleb as something of a maverick and a lone ranger. Even beyond the plain text of the Torah, there is a tradition that Caleb — during the reconnaissance mission — at one point drew his sword and quite literally threatened the other Spies with violence.3 Tradition likewise assigns to Caleb the sobriquet Mered [literally, rebellion] on account of his willingness to defy the Spies’ majority view.4 Joshua, by contrast, apparently started out as part of the Spies’ camp. The Biblical text does not record him as having dissented either from the Spies’ assessment that the Jewish people could not overcome the Canaanites, or from the Spies’ defamatory characterization of the Land. Thus, one might even argue that Joshua’s actions lent initial support to the Spies’ problematic reports (whether tacitly or explicitly). Again, it wasn’t until the people were engaged in outright rebellion that Joshua broke ranks and publicly joined Caleb in protest.

The plain Biblical text does not give insight into Joshua’s motivations. But rabbinical tradition, at least, is clear that Joshua disagreed with the Spies’ assessments from the get-go. We are meant to understand that — behind the scenes — he felt exactly as Caleb did.5 And yet, he stayed behind the scenes and chose to keep that disagreement behind closed doors, until essentially the last minute. Why?

What this suggests to me is that Joshua was trying to effect change from within. Joshua no doubt understood that even if he and Caleb stood up and loudly disagreed with the Spies, they’d be outvoted in the eyes of the people. And Joshua no doubt understood that the Jewish people would not enter into the Land of Israel if a supermajority majority of their chosen representatives were dead set against doing so (10-2 isn’t exactly a close vote). And so it seems reasonable to suppose that Joshua was trying to moderate the Spies’ views and to get them onboard with entering into the Promised Land. Caleb’s approach to dealing with the Spies was to threaten them with violence, follow his own itinerary, and to make clear that they didn’t speak for him. Joshua, it seems, preferred to keep disagreements behind closed doors and worked instead to try and change their hearts and minds.

Admittedly, this is conjecture on my part. But my reading is strengthened when we consider that Joshua had a moderating effect… on Caleb. We can see this by contrasting Caleb’s initial expression of dissent with his later joint statement with Joshua. After the Spies delivered their initial (and non-defamatory) report of the Land, Caleb responded by telling the people: Let us ascend at once, and take possession of the Land; for we can surely conquer it.6 That is, Caleb spoke with peppy enthusiasm and unqualified optimism, telling the people that they are without a doubt up to the challenge.

Once Joshua joined Caleb, things started to look very different:

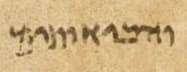

And Joshua son of Nun and Caleb son of Jephuneh, of those who scouted the land, rent their clothes. And they spoke to the entire assemble of Israel, saying:

The land which we have crossed to scout out — the land is an exceedingly good land. If God is pleased with us, God will bring us into this land and it He will give it to us: A land that is secreting milk and honey. Only, do not rebel against God — and do not fear the inhabitants of the land, for their are our bread; their defense has departed from them, and God is with us — do not fear them!7

If Caleb started out by addressing the people with exhortations and platitudes (We can do this! Yes we can!), once Joshua was at his side, the messaging sharply evolved. The two dissenters delivered a forceful, eloquent, and reasoned appeal to the people — rooted in evidence, values, and responsibilities:

For starters, this second message directly responded to the substance of the Spies’ report — showing that the speakers take the people and their concerns very seriously. Caleb’s first exhortation was unqualified — we can do it! — this other one acknowledged that the success or failure of the mission depends on circumstances beyond the people’s control (we can do it… but only if God is pleased with us). They honored and validated the people’s misgivings. Likewise, this second message drew on facts, rather than rhetoric. The speakers reminded the people about the goodness of the Land, and they reminded them of the materially beneficial reasons to take the (real) risks of entering into Canaan. Finally, and perhaps most critically — whereas Caleb’s initial message to the people was an anthropocentric one (we can do it), the second message changed in an important way: Caleb and Joshua reminded the people that their fate was entirely in God’s hands. And they likewise remind the people not only of their hoped-for benefits, but their very real responsibilities (don’t you dare rebel!).

***

… Sadly, it didn’t work — Joshua and Caleb failed to stave off the rebellion. But Caleb’s shift in messaging is striking — and this is a shift that I believe we ought to credit to Joshua. And again, what this suggests to me is whereas Caleb was comfortable being a vocal dissenter, Joshua worked to persuade and build coalitions — he was someone who tried to lead change from within. And even if he did not succeed to move the Spies, he certainly seems to have left his mark on Caleb.

III.

We tend to roll our eyes at those who try to create change from within. This strategy doesn’t always succeed, to put it mildly. But the example of Joshua suggests that leaders nonetheless have to try. Indeed, Judaism does not exactly view being a maverick as an a priori virtue or something that is necessarily praiseworthy — to the contrary, tradition looks askance at those who enthusiastically separate themselves from the ways of the community.8 This, in turn, sets up a subtle critique of… Caleb. Yes, Caleb was right about the Land and the Spies were wrong. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that his approach was well-suited for leadership. Change doesn’t always start at the barricades — sometimes, it requires the board room. Dissent is not inherently patriotic. Threatening your compatriots with violence is… not always prudent (even if you’re right and they’re wrong!). Breaking ranks is not always a good thing; to the contrary, it’s often a way to forfeit one’s share in the World to Come.

That’s not to say that coalition-building and trying to create change from within is free from moral danger. There’s no shortage of people who sit in the halls of power and tell themselves that they’re there to be the responsible adults in the room… that they’re there to moderate a leader’s worst instincts… or that they — like Queen Esther — are in position to make a principled stand when the chips are down. And sadly, far too often, these well-intentioned men and women fail to meet their lofty goals: They don’t end up checking power so much as they end up corrupted and co-opted by it. They end up falling in line to bolster bad leaders, sacrificing their values, their integrity, their hard-earned reputations in the process.

But here’s the kicker: Unlike the well-intentioned people who sacrificed their honor in order to stay in power, Joshua actually walked away when it counted. He remained in conversation with the Spies until it was no longer morally or strategically possible to do so — he chose to walk away at the right time and for the right reasons. Redlines were being crossed,9 and so it was necessary and important for Joshua to break ranks and to make a principled stand.

Some would-be leaders are lost to history because they are too eager to go at it alone or too quick to separate themselves from the community they’re supposed to serve; others are lost to the world because they refuse to take a principled stand, and are slowly absorbed into a miasma of immorality through a million tiny soul-crushing compromises. But Joshua — it seems — got it exactly right. He tried his best to work from within, even if doing so was uncomfortable; he was prepared to walk away if it became necessary (even if that was uncomfortable) … and in fact did so.

By initially remaining in the company of the Spies, Joshua may not necessarily seem — to us — like a profile in courage. But having done so reveals exactly why he was well-suited to lead the people to their ultimate destination.

IV.

Someone helpfully asked me after my last post about the Spies: Who are the Calebs in this day and age? And I answered honestly that I didn’t know of many. But fortunately, I know a lot of Joshuas.

The single most consequential investment that we’ve made in the realm of social change is in a remarkable platform called MAOZ. MAOZ is an Israeli NGO which works to empower and accelerate leaders from across Israel’s many diverse communities, geographies and sectors — giving them the skills they need to thrive and succeed. In other words, MAOZ finds the Joshuas — the leaders who are interested in making a difference (and not merely making a statement): Principled and moral people who understand that they can’t effect change from within their narrow bubble and within the comfort of their community — and who feel acutely the necessity of fellowship and coalition. And most importantly, MAOZ takes these leaders and works to make them collectively powerful — it has an unflagging commitment to helping these leaders form trusting relationships with one another… ensuring, for example, that secular Arab advocates, religious Jewish bureaucrats, Haredi mayors, and tattooed entrepreneurs from Tel Aviv can all sit together, work together, and create change together.

MAOZ has been doing this for over a decade at this point. And at the moment, MAOZ’s boasts a Network of over a thousand leaders from all over Israel. This Network has produced some remarkable success stories… all of which attest to why Joshuas matter… why we need Joshuas.

I can’t say that we’ve figured it out. Far to the contrary, the Network is a fragile organism — trust is difficult to generate and easy to destroy. At any given moment, a member of the network can ignite a fire and undo a decade’s worth of hard work. And the Network exists downstream of all the toxicity that characterizes of contemporary politics.

The most important thing that we can do is to ensure that this fragile organism called the Network becomes bigger, stronger, tougher, and more resilient. And if I’ve piqued your interest and you’d like to learn more about what that might entail (and are interested in helping out), please do drop me a line.

***

… When they write the history of this age, they might tell the story how humanity placed itself at the mercy of a bunch of well-intentioned mediocrities, genuinely bad people, and good people who should have known better. But there are some remarkable Joshuas who are trying to write a different story. And they need our help.

V.

Maybe if the world were full of Calebs, we wouldn’t need Joshuas. If we all worked to cultivate faith, and if we were all clear-eyed about value, then maybe we wouldn’t have to shake hands with the Spies… much less try to work with them (or through them). Maybe we’d have the luxury of moral purity.

But humans are humans. And Calebs are in short supply. And that being so, the Torah wants us to understand that pure-hearted zealots and righteous dissenters do matter and are deserving of our thanks and praise… but we need leaders who are cut from a different cloth. The Torah tells us to look to leaders who don’t try to go at it alone… to look those who try to lead change from within, even as they bring an unshakeable moral compass to smoke-filled rooms.

Prescience and foresight and moral clarity are all undoubtedly important, but the diverging fates of Caleb and Joshua suggest that leadership requires something besides being really smart, or having the courage to tell the folks in the majority that you’re right and they’re wrong.

Because at the end of the day, leaders aren’t accountable for being right. They’re accountable for doing good. That’s why we need leaders who understand the difference between making a statement and making a difference. And if we’re lucky enough to find such people, hold on tight and give them all the help you can.

Because those are the people who will lead us to the Promised Land.

As I noted in a previous post, this is not my original interpretation of Joshua’s role in the story of the Spies. Credit for that belongs to my rosh yeshiva — one of heads of the religious seminary where I studied for a gap year.

The first presidential election in which I voted pitted then-Senator Barack Obama against Senator John McCain. Mr. McCain’s brand boiled down to the term maverick. He was known as someone who defied his party regularly, bucked conventional wisdom, and very much marched to the beat of his own drum.

Mr. Obama took a similar tack. He ran a hard-fought campaign against then-Senator Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination, and prevailed against the odds. And one of the contrasts he drew with Ms. Clinton concerned their records regarding the War in Iraq. As a Senator, Ms. Clinton voted to authorize the American invasion of Iraq (along with the majority of Democrats in the Senate). At that time, Mr. Obama was serving in state government, and he had given a speech expressing opposition to the war. Some five years later, Mr. Obama used his early and consistent opposition to the war to great political advantage.

And so, for all the very real differences between Messrs. McCain and Obama, both candidates marketed themselves to the American people in the same way: They were both trying, in a sense, to claim Caleb’s mantle.

Bamidbar Rabbah 16:14.

See Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sanhedrin 19b (commenting on I Chronicles 4:18).

See Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sotah 35a.

Numbers 13:30.

Numbers 14:6-9. Note also that the Torah places Joshua’s name ahead of Caleb’s — subtly suggesting that he, not Caleb, is the driving force behind these remarks.

See, e.g., Moses Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, The Laws of Repentance 3:11 (“One who separates himself from the ways of the community — even if he commits no sins, but merely divides himself from the people of Israel, and does not fulfill mitzvot with them, or share in their sorrows, or participate in their communal fasts — rather, simply goes on his own path, as if he were of another nation and not of Israel … he has no share in the World to Come.”). It don’t mean to suggest that this prohibits dissent or anything of the sort — but at the very least, it asks us to think long and hard before walking away, breaking ranks, and defying consensus.

As my rosh yeshiva pointed out, in seeking to return to Egypt, the mob was trying to undo the Exodus — thus attacking the very foundation of the Jewish covenant.