To Case the Promised Land

“Gonna be a twister to blow everything down / That ain't got the faith to stand its ground.”

It’s the ninth day of the fourth month, a little more than two years after the Jewish people left Egypt. The Jews are camped on the edge of the Promised Land, awaiting a report from the twelve spies they’d sent to scout out the Land of Canaan.

The Spies return and duly inform the assembled nation that the Land is a goodly one but that taking possession of it will be no easy task.

One of them — Caleb, the son of Jephuneh — breaks ranks: He reassures the anxious people that with God’s help, they can and will conquer the Land notwithstanding the very real dangers.

The remaining spies react harshly. They flatly contradict Caleb’s assessment and tell the Jews that the Promised Land and their ultimate destination is a “land that eats its inhabitants” and is populated by people with comparatively overwhelming strength.

The Jews respond with an outpouring of tears and anxious laments, and — ignoring the protestations of their horrified leaders — even take steps to return to Egypt. Caleb (joined now by Joshua) tries vainly to stop the mob, only to be met with threats of violence.

In response to this unprecedented behavior, God metes out unprecedented punishments: Excepting the brave dissenters, the Spies are struck down where they stand for having slandered the Land. And as for the rest of the nation? They are condemned to wander the desert for forty years, until the entire generation dies out.

***

Three thousand years later, the dynamic is sadly all too familiar. Bad leaders, drawn from every conceivable sector of society, seem hellbent on consigning us to the Wilderness, even taking us back to Egypt. The names have changed, the technology is improved. But it’s the same old story: Our ancestors’ downfall — the ur-tragedy which sets the tone for all subsequent ones to have befallen the Jewish people — appears to be playing out all over again. History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes…

It is impossible to overstate the pain which has characterized the past year. And there is, candidly, no end in sight. There are no good choices to be made.

But this much is clear: We cannot go back. We cannot return to the Wilderness, to Egypt, to the way things were before.

Our ancestors stumbled that we might stand; their failures are recorded so that we might be lucky enough to escape the gravitational pull of History, make original mistakes, and write a new Song. This starts by looking backwards and unpacking how and why our ancestors went astray — not self-righteously and self-confidently, but with a spirit of vulnerability and humility. And then it requires us to look hard at Caleb — the man who had the fortitude and foresight to resist the Spies, and who tried to chart a faithful and alternative path for Jewish history.

We owe it to them and we owe it to ourselves to try.

I.

It’s tempting to treat the Spies as evil incarnate and nod with satisfaction at the bare Talmudic assessment that they forfeited their share in the World to Come1: The Spies were a bunch of inveterate liars. They gleefully and intentionally incited a panic and thereby doomed an entire generation. Who cares why? They were just bad people.

Could be. Maybe some leaders would set the world on fire for personal gain or they derive pleasure from other people’s suffering. Maybe that’s the story of the Spies.

But there’s a danger to adopting such a narrative. It transforms the Spies into an abstraction, a foreign body, or an errant weed — something that we can easily dismiss or simply pluck out. I’m not a sociopath. I’m not a nihilist. I’m a good person. I would never do what they did. I would have spoken up. I would have resisted. And so we lull ourselves to sleep at night, comforting ourselves with the unearned certainty that if we’d have been there, we would have been a Caleb or a Joshua… not one of the bad guys.

… That’s the easy way out.

The harder task — and certainly the one that Judaism expects of us — is to take sinners and their sins a bit more seriously and with a bit more humility:

The Talmud, for example, records a dream by a fourth century scholar, in which the rabbi converses with the spirit of a singularly wicked ruler in Jewish history.2 The rabbi reports his shock at discovering that the king (rather than being a vulgarian ignoramus) was profoundly learned and intelligent, even well-versed in Halachic minutiae. Shaken, the rabbi asks the king how and why someone as smart as he was could have engaged in such grievous sins… obviously, he must have known better! The king’s response? If you’d been there, you’d have raced to keep up with me while I did it.

The lesson is clear: We should not engage in self-flattery at the expense of our predecessors. We should not believe ourselves to be inherently better than they were, or insusceptible to the sins which them tripped up. If they sinned, stare hard at their sin and think about it from an empathetic and humble perspective. Start from the premise that these were good people – great ones, even! – and then try to understand how and why they went astray. And then understand that the same thing could easily befall us.

We tell ourselves that if we’d been there, things would have turned out differently. We would have been on the right side of history. We’re asked to try exactly the opposite approach: If we’d been there, we’d probably have sinned in exactly the same fashion. And only by internalizing this point can we have any hope of avoiding our ancestors’ mistakes.

II.

The popular conception of the Spies is that they lied about the Land for nefarious reasons. But if we take up the invitation — the imperative, really — to view the Spies as something other than cartoon villains, things suddenly start to look extremely different:

A.

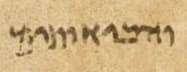

Start with the substance of the Spies’ report. As I read it, the essence of their defamation boils down to four Hebrew words: Eretz Ochelet Yoshveha Hi – “it is a land which eats its inhabitants.”3 I’ll admit that I don’t take exception to the epithet, in part because it sounds like something out of the greatest performance of Bruce Springsteen’s greatest song (listen to this and thank me later). But either way, it’s hard to see how this description of Canaan is so problematic considering that it’s the logical and natural extension of the Torah’s own description of that selfsame land.

That is, in the eighteenth chapter of Leviticus, God admonishes the Jewish people:

Do not profane yourself with all of these things. For through all these things, those nations that I send out before you became profaned. And the Land became defiled, and therefore I accounted for its iniquity — and the Land vomited out its inhabitants. And you shall observe My laws and My decrees and you shall not do any of these abominations — neither the citizen nor sojourner dwelling in your midst. For all of these abominations were done by the people of the Land before you — and the Land became profaned. And do not let the Land vomit you out when you profane it — as it vomited out the nation before you.4

The Torah twice emphasizes that the prior inhabitants of Canaan were thrown out — literally vomited — by the Land, and cautions that this could happen to the Jewish people as well. Of course, to vomit out something necessarily implies that it had previously been ingested. Thus, the clear and unmistakable inference of a Land vomiting out its inhabitants is that the Land can in fact eat its inhabitants.

Indeed, the Talmud explicitly and unambiguously defends the Spies against the accusation that they lied: While their report of the Land was defamatory, that doesn’t necessarily mean it was false.5 In other words, the Spies may not have been punished for publishing fake news so much as for leaking classified information; their crime may have been saying the quiet part out loud.

B.

But why did they do it? The Spies clearly wanted to prevent the Jewish people from entering into the Land. Why else would they have offered such a vitriolic response to Caleb’s exhortations and his attempts to rally the people?

The Lubavitcher Rebbe and Emmanuel Levinas each offer a compelling interpretation of the Spies’ motivations,6 and both their readings boil down to this:

Their sin was rooted in an excess of morality and a desire to avoid the messy contradictions that inhere in taking power. In Diaspora, in Exile, in the Wilderness, the Jews lived in a semi-mystical state — their every need provided for by God, their daily lives determined by God, and so on. Entering into the Land meant giving that up that privileged relationship and becoming tainted by the complexities and challenges of everyday life. When you go from subsisting on manna from heaven to having to grow your own wheat, you have less time to focus on Torah study; when you need to conquer a land by force, well, you have to use force. The Spies wanted to preserve the spiritual integrity of the Jewish people; they feared the consequences of entering into the Land:

We’re doing fine in the Wilderness. Deus providebit. Why give that up?7

What it means, in essence, is that the Spies were not these Rasputin-like figures who hypnotized the people or terrified them with fake news and false reports. Actually, all they did was share their impressions of Canaan, hoping to help the people avoid making what they thought would be a grave mistake.

C.

I stated at the outset that Judaism expects us to approach history through a lens of empathy and humility. But Judaism does not expect us to forgo moral judgment and abdicate our God-given responsibility to distinguish between right and wrong. To understand, to sympathize, and to empathize is not to justify.

And so even if we ascribe to the Spies the best of motivations, we are bidden to reconcile that with the reality that the Spies sinned – damningly so! – and forfeited their share in the World to Come for their crimes.

The wrongness of their actions becomes apparent when we contrast the Spies’ defamatory description of Israel (it is a land which eats its inhabitants) with their initial description of the Land. That is, the Spies first characterize the Promised Land as the Torah consistently does: “Zavat Chalav U’Devash” — a land of flowing milk and honey. Like the defamatory description, this anthropomorphizes the Land: The term “zavat” is used in the Torah to describe bodies that are secreting or discharging something.8 Honestly, linking the Land of Israel to an improper bodily function is hardly the most flattering comparison, and yet it’s the key to understanding the problem here:

The Torah describes the Land of Israel principally in terms of its outputs. Milk and honey — these are things that the land generates and produces. By contrast, the Spies describe the land in terms of what it takes — it eats its inhabitants9 In other words, they framed the journey into Israel in terms of the sacrifices that the people would be making and what they would be giving up — rather than focusing on all that the Jewish people stood to gain.

Oscar Wilde needed a single sentence to make a point that took me thousands of words: A cynic, he writes, is a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.10 And in that sense, we can see clearly how the Spies went astray. While it may seem like small potatoes, the Torah wants us to understand that this is a very big deal. If damnation and Exile stem from cynicism, redemption hinges on the ability to discern value.

Easier said than done, and therein lies the point.

III.

It turns out that it is terrifyingly easy to forfeit your share in the World to Come. You don’t have to be a sociopath, a nihilist, or even a liar: You just have to have good intentions and give an honest account of what you experienced.

And in this light, it’s much harder to flatter ourselves as a brave dissident. If we’d been there, can we honestly say that we would have been able to resist the Spies? Can we honestly say that we would have gotten it right? Or, said differently: How would we be expected to know what to do? How would we get it right? What would give us the courage to stand apart from the majority and resist fear-mongering by our leaders?

And this brings us back to the present day. We’ve crossed into the Promised Land and we have seen and experienced the overwhelming goodness of the Land, alongside the considerable sacrifices that living here has entailed. There is not a man, woman, or child living in the Land of Israel who could possibly ignore or deny the inputs.

And now — louder than ever — we hear contemporary echoes of the Spies’ ancient sin in the members of our community, chiefly from those who declare themselves implacably opposed to Jewish statehood and sovereignty. They see what it has looked like to exercise power, sovereignty, and responsibility in our historical homeland. They look at what it has taken to live in our homeland. And they have concluded that it’s not worth the price of admission. They tell us that this is a land which eats its inhabitants. They tell us that we are sacrificing our loved ones. They tell us that we are destroying our souls. They tell us that we’re grasshoppers in the scheme of things — just who do you think you are to think you’re up to this challenge?

And after the week we’ve had, the year we’ve had, the decades of heartbreak and conflict and compromises and mistakes… it’s almost even possible to think the unthinkable. What if they’re right?

How — amidst all that we’ve experienced — do we avoid succumbing to despair and to cynicism? How do we avoid a return to the Wilderness, to Egypt, and to the way things were?

IV.

In the story of the Spies, there was only one man who had it right from the very beginning: Caleb, the son of Jephuneh.11 And perhaps by examining his story, we might be able to answer the foregoing questions. If he avoided the traps that befell our ancestors and withstood the Spies’ cynicism, then presumably he provides a template for how we might do the same.

Caleb isn’t a well-rounded character in the Biblical text. We don’t really get a lot of insight into his motivations. All we have to go on are his remarks to the people and God’s assessment of his character: Caleb stood apart, says God, because he had a different spirit with him.12 The text certainly bears out this assessment, Caleb’s attempts to rally the people are shot through with apparent optimism: Let’s go! We can do this! When the Spies disparage the Land, Caleb does not contradict anything that they’ve said — all he does is remind the people it’s a land flowing milk and honey and the land is good — very, very good! He talks about outputs rather than inputs. And he insists again and again that with God’s help, the people are up to the challenge of taking possession of the Land. The Spies talk about cost; he perceives and emphasizes value. Caleb, in other words, is a man who has overwhelming and abundant faith.

But this presents two interrelated and mutually reinforcing problems:

First, the Torah’s description of Caleb is telling — he had with him a different spirit. There seems to be something almost passive and predetermined about Caleb’s character arc. His sense of hope and optimism was conferred on him — it’s less about what he did than the fact he was lucky enough to be wired differently. He was seemingly graced with faith.

Second, and building off the foregoing point, how exactly can we expect Caleb’s faithfulness to resonate with people who lack that other spirit? The things he says aren’t likely to persuade those whose faith is wavering or altogether absent.

Viewed through a contemporary lens, it’s easy to see how Caleb’s answer feels spectacularly unsatisfying. Even the most faithful have to admit that it feels difficult to believe, after the events of the past week, month, and year. We are in the depths of grief and anger and horror. A sense of helplessness abounds. To talk about value and expected gains in the face of the overwhelming and immediacy of the cost feels insensitive at best and obscene at worst. This feels hardly the time and place for affirmative exhortations.

If a Caleb showed up today to tell us don’t worry, it’s going to be fine, God help us, but I fear we’d probably try to stone him too…

V.

But maybe, we don’t have to end with that. Because even if Caleb’s faithful appeals fell on deaf ears, there’s something else that he did which may prove instructive for us as we struggle through this dark and painful night:

According to the Talmud, at some point during the Spies’ reconnaissance mission, Caleb took leave of his peers and went to pray at the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron. There, he prayed for the strength to stand apart from the Spies… to not be swept up in their way of doing things.13 In other words, Caleb sought faith. When overwhelmed by data about cost, he didn’t want to lose sight of the prize. He wanted to believe.

This is a radical point. Some might argue that the capacity for faith is innate — some people are wired for belief, and others aren’t. Some might also argue that faith is dependent on external circumstances and things beyond our control.14 I don’t disagree at all — accidents of birth and of circumstance appear very relevant to belief. But these things don’t have to be determinative.

Caleb’s actions invite us to see faith a bit differently — as something which stems from human agency:

The Talmud helps us understand that Caleb had faith because he took steps to cultivate faith. He had the presence of mind to acknowledge his deficiencies and vulnerabilities: He knew he needed help and reinforcement in order to resist the pull of his fellow Spies. And to rectify that, he traveled to a locus of Jewish memory and identity within the Promised Land: The burial-plot of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs.

This suggests that faith can be grown. Faith can be learned. Faith can be strengthened. There are things we can do to ensure that it flourishes. There are things we can do to enhance it. There are things we can do to train ourselves, muscles that can be developed, in order to believe. We can train ourselves to see value — even as we take note of cost.

And that’s what we must do, in moments of complete and utter brokenness — when value seems illusory, and when faith feels like an impossibility. In moments like these, when hopeful exhortations would fall on deaf ears and may even be counterproductive, Caleb invites us to (re)-build our capacity to believe.

That includes, for example, letting go of determinism and monism. It includes shattering idols — opening our minds and disintermediating between ourselves and the things that matter. It includes practicing radical curiosity, radical questioning, and radical empathy. It includes working hard to see what we might otherwise overlook. It includes time in community and in fellowship with one another. It also includes stepping away from the group and finding time out of time and space out of space to reflect, to pray, to be vulnerable, and alone. It also includes — as Caleb did — turning to our heritage and to our ancestors.

Faith can also be generated by doing the hard and messy Work that sits at the heart of a covenantal community. We repair our shattered faith by helping one another, laboring alongside one another, showing up for each other, and mourning together. Maybe, God willing, one day we’ll even be privileged to celebrate together. But for now, we will keep digging until our fingers are raw and bloody, trying as hard as we can to do right by one another, and fighting with every fiber of our being for our most basic values.

If we can do this, maybe we’ll be able to make original mistakes instead of repeating our history. If we can do this, maybe the Land won’t vomit us out. If we can do this, we might avoid another generation lost to the Wilderness. If we can do this, maybe… just maybe… we might teach our eyes to See, our ears to Hear, and our souls to Believe.

Mishnah Sanhedrin 10:3.

Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sanhedrin 102a.

Compare Numbers 13:27-29 and 13:32-33. The former is the Spies first report; the second is the Spies defamatory one:

As I read it, each report follows the same broad structure: (1) a prefatory clause describing the nature of the spies’ report [red]; (2) a description of the land itself [yellow]; (3) a description of the prowess of the inhabitants [green]; and (4) a description of the gargantuan size of those same inhabitants along with some other details [blue].

And they’re likewise similar in terms of substance. The first report includes a touch more detail about who lives where; the second has a bit more detail about the prowess of the Land’s inhabitants. But in the second report the sole point of substance which differs from the unproblematic initial report is their characterization of Canaan as a land that consumes its inhabitants. Everything else that the Spies said in their second report neither contradicts nor undermines their initial report.

Leviticus 18: 24-28.

Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sotah 35a.

See Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, Torah Studies: Discourses by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson (adapted by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks), pp. 245-51; Emmanuel Levinas, Nine Talmudic Readings (trans. Annette Aronowitz) pp. 51-69.

In this respect, the story of the Spies corresponds to the famous story (see Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Shabbat 88b), wherein the ministering angels questioned God’s decision to give the Torah to the Jewish people. The angels were concerned, it seems, that the people would fail to render sufficient honor to the Torah — and that their failures and shortcomings might even therefore bring the Torah into disrepute. The Spies, in this reading, were analogously concerned for the integrity of the Jewish people’s souls.

It’s telling, however, that neither the angels’ nor the Spies’ concerns carried the day. In both instances, God — knowing full well the fallibility of the Jewish people — nonetheless expects that we rise to the challenges of observing the Torah and living responsibly in our homeland.

See generally Leviticus 15.

The contrast becomes even clearer when we reconsider Leviticus 18. Did the Land eat its inhabitants, before vomiting them out? Obviously. But the Torah chooses to leave the fact of their consumption as subtext, while instead focusing on their having been expelled — talking about outputs rather than inputs.

The textual choice is also revealing inasmuch as there are plenty of occasions in which the Torah explicitly describes the earth as eating or swallowing someone (e.g., Numbers 16:32), yet never does so with respect to the Land of Israel.

Oscar Wilde, Lady Windermere’s Fan. The flip-side, of course, would be that a freier is someone who knows the value of everything and the cost of nothing. And we are bidden to sit uncomfortably in between, balancing both cost and value simultaneously.

To be fair, Joshua — Moses’s successor — was also one of the Spies, and he (like Caleb) is also a hero of the story. But if we read Numbers 13 and 14 carefully, we will see that Joshua is not recorded as having dissented from the Spies’ harsh and critical assessment of the Land. As one of my rabbis from yeshiva points out, the text does not indicate that Joshua broke ranks and stood alongside Caleb until the people actually take steps to rebel.

Numbers 14:24.

Sotah 34b. See also Levinas pp. 58-59.

This is the essence of Satan’s challenge at the beginning of the Book of Job 1:10; 2:4-5: Job only believes because he has it so good. The inverse of that formulation converges on the same point, though: There are no atheists in foxholes.