The Gallery

"They lived and they died / They prayed to their gods / But the stone gods did not make a sound / And their empire crumbled 'til all that was left / Were the stones the workmen found."

I.

Seven centuries before the Common Era, a Middle Eastern despot invaded the Jewish state, unleashing ferocious violence upon its inhabitants. The Bible tells how King Hezekiah faced off against Sennacherib’s hordes and was rescued at the last minute by divine intervention. The Assyrian invaders also made contemporaneous records of their own, telling their version of the story.

We wrote ours on parchment — black fire upon white — and taught it to our children. They carved theirs in stone and set them in the walls of their ruler’s palace.

These records, the so-called Lachish Reliefs, now sit in the British Museum. They are a series of carvings depicting the sack of a small Judean fortress in overwhelming and excruciating detail:

Captives are paraded out of the city past the impaled corpses of its defenders. An Assyrian soldier cuts the throat of a kneeling Jewish chieftain. Assyrian soldiers are flaying two of the survivors; the next victim stands watching, flanked by his two young sons — and he throws his arms up to heaven in anguish, horror, and disbelief. And there, right next to them, a Jewish woman is ushered out of the city, never to return — arms wrapped around her two young children.

It’s pathological, frankly. Our enemies can’t “just” try to commit a genocide against us… they have to also document it in technicolor: Hamas’s live-streamed atrocities; the Auschwitz Album; the Einsatzgruppen photographs; the Arch of Titus; the Judaea Capta coins — the Lachish reliefs are just the first example of this barbarism.1

And even if you’ve never been to the British Museum or have never laid eyes on a piece of Assyrian art, you’ll find the images impossibly and unbearably familiar:

All it takes to undo a person is to see the world as it really is.

The massacres at Lachish and Nir Oz are separated by seventy kilometers of distance and nearly thirty centuries of history. But the distance between these scenes is — in a theological sense — infinitesimally small.

II.

When confronted by horror such as this, it’s only natural to reach for comfort. And when contemplating the Lachish Reliefs, nausea gives way to the knowledge that all that remains of Sennacherib and his empire are those carvings. All that remains of the pharaohs who enslaved us, oppressed us, and drowned our baby boys are a bunch of rocks and well-preserved corpses. The Seleucids. The Romans. The list of those who rose against the Jewish people is long — and all that’s left of them is slowly decomposing inside the walls of a stuffy imperialist institution, beneath a glass ceiling stained brown by the pigeons that roost atop it.

I don’t doubt that those who currently seek our destruction will one day be entombed in the Gallery as well.

But that’s cold comfort lately.

Because I walked through the British Museum wearing a baseball cap. And at synagogue the next day, I had to go through a security check. The advertisements on the flight urged Jewish Israelis to try and blend in abroad. Dozens of my countrymen are still held captive by a genocidal death-cult.

It would be a mistake to use the Gallery as a metaphor for Jewish triumph.

Because the Gallery — much like life itself — doesn’t lend itself to comforting narratives about Jewish survival or wrenching tales about Jewish victimhood.

It lends itself instead to uneasy and complicated truths about Jewish existence.

III.

Religiously speaking, the massacre of Lachish took place at a high-water point of Jewish history. We had sovereignty in our homeland; the Davidic line was in power and the throne was occupied by an exceedingly righteous king; the Temple was intact; the priestly line was intact.

But the Jewish people nevertheless experienced horrors on par with October 7th. All of our infrastructure was insufficient to prevent humiliation, atrocities, and mass kidnappings. Which is to say, Lachish demonstrates that even if you do everything right, it still won’t be good enough.2

If the Grove reveals the implacability of our enemies, the Gallery demonstrates the limitations of Jewish sovereignty:

In every generation they do in fact rise up against us. And no matter how hard we try, we can’t expect it stop.

We fell well short of that exacting standard on October 7th. Those massacres were preventable; that they happened is due to unforgivable and inexcusable political, military, and civic failures at every level.

I have no doubt that we will learn from those mistakes: We will work harder and we will do better. But chances are that despite our very best efforts, scenes like these will recur again and again — virtually no matter what we do.

And so the lessons of Lachish mean that we need to think seriously about what we can realistically ask of Zionism.

But to do that, we need to smash some idols first.

IV.

At the heart of idolatry is confusion about means and ends. We sin when we place proscribed intermediaries between us and God (e.g., graven images); we likewise sin when we treat mere instrumentalities as ends in and of themselves.

This, according to Maimonides, is how idolatry came to the world. Not long after the world was created, humanity began to worship the sun, moon, and stars out of a well-intentioned but misguided belief that these extraordinary things — having been created by God — were themselves worthy of praise and service.3

This mode of thinking persisted until Abram came along. Per Jewish tradition, Abram — like his peers — was also overawed by the mysteries of the cosmos and the majesty of the created universe. However, he didn’t stop there; he kept looking. The things Abram saw led him to something greater — something much more magnificent and transcendent: The Cause of all causes… the Reason of all reasons. In other words, Abram sought the End — and he didn’t get distracted by the beautiful and terrible things he saw along the way.

This is the foundation of ethical monotheism and of the Abrahamic covenant with God.

And yet we have not succeeded to wholly eradicate the scourge of idolatry.

We lapse into idolatrousness whenever we elevate a means to an end… when we forget why we do something, and allow ourselves to become invested in doing it for its own sake.

There are too many examples of this to count, but one idol has proven particularly durable — that of safety.

V.

Many serious thinkers have argued that October 7th marks the death-knell for the religious, political, and ideological project underpinning the State of Israel: October 7th discredits Zionism itself, because Zionism promised us safety and a safe haven. They are doubly mistaken: Safety isn’t something that is attainable and — regardless — safety is not the point of Zionism.

The longing for Jewish safety has always helped fuel Zionism. Almost a century before the birth of Theodor Herzl, the French philosopher and provocateur Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote stirringly about the physical dangers endemic to Diaspora and encouraged the creation of a Jewish State. Early Zionist writers took up these same themes, pointing to crimes such as the Dreyfus Affair and the Kishinev pogrom to justify the need for Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel.

But Zionism could never have promised the Jews safety, because safety is not something within anyone’s power to offer. The State of Israel could never have fulfilled a post-Holocaust ethos of never again, because never again is something only God can promise. Sovereignty is not a magical talisman that can immunize us from fear, from threat, from vulnerability, from compromise.

And so we should not have needed Nir Oz to teach us what Lachish had already made obvious:

If Hezekiah couldn’t do it, we should not have expected more from David Ben Gurion. If the First Temple wasn’t sufficient to protect us from our enemies, we can’t very well ask that of the Kotel. The Knesset, Iron Dome, the IDF, and Israel’s remarkable citizenry — these things are extraordinary and wonderful and powerful and they matter deeply. They make us safer, yes, but nothing — truly, nothing except for God — can make us safe.

… And more to the point, while it is legitimate and important to work towards safety, physical security has always been a strategy in service of a higher goal.

Bury once and for all the idolatrous notion that the State of Israel exists to prevent Jews from getting hurt. Uncouple — finally — our national, religious and communal liberation from the human desire for safety.

… If we can do this, then maybe we have a chance at articulating why Israel and Zionism actually matter… and what we should be doing differently as a result.

VI.

Look past the means and start with the End: Return to the foundational first principles of Judaism.

To paraphrase Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, Judaism is not a monastic or individualistic religion wherein the focal point is an individual’s personal relationship with God. Judaism instead aims at a collective, covenantal bond with God. Judaism is about a critical mass of people living justly, righteously, distinctively — proving that it can be done and offering a template for others to follow.

The State of Israel, therefore, does not exist to maximize a given individual’s happiness or safety or comfort; rather, it is here to help Jews succeed in our collective mission as Jews.

This is why it is both normatively wrong and practically impossible to disentangle Judaism and Zionism;4 this is why the State of Israel matters — because it is our people’s best and only chance to fulfill our collective and covenantal mission.

***

I don’t think Judaism insists that all Jews live in the Land of Israel; rather, only that enough Jews live in the Land of Israel. And by the same token, I don’t want to engage in gratuitous Diaspora-bashing. The Diaspora (of which I am a product) has produced extraordinary Jewish individuals, marvelous Jewish institutions, and thriving Jewish communities. Diaspora Jews have made invaluable contributions to Torah, to philosophy, to the sciences, and to the arts — things that instantiate the very best of Jewishness… things which are vital and important to the Jewish people as a whole… things that make the world a better place.

The Jewish people would be greatly diminished if we ceased to have a critical mass of Jews living in the Diaspora. This isn’t because the Diaspora is essential to sustaining the State of Israel politically, economically, or philanthropically; rather, Diaspora offers a valuable spiritual role to play vis-à-vis the Jewish people as a whole.

And [not but] the socioeconomic, political, and cultural conditions of Diaspora don’t allow Jews — as a people — to become who they need to be as a people. How can we — as a people — live loudly, exuberantly, and full-realized Jewish lives in places whose cultures, systems, and institutions conflict with Judaism’s core values? These are formidable technical obstacles that individual Jews can (and many of them do!) overcome as individuals. But they are insurmountable obstacles for a nation as a nation.

Again: I am awed and inspired by the achievements of individual Jews living in Diaspora. And [again, not but] the Jewish people can never be the people we are collectively supposed to become living downstream from someone else’s culture, politics, values, and economy. We simply can’t do it by playing somebody else’s game and on somebody else’s turf.

VII.

Seen in this light, Zionism is about reducing certain kinds of difficulties — i.e., those endemic to Diaspora — in order to give the Jewish people as a people the chance to be who we are supposed to be as a people.

There are, for example, relative physical protections that are afforded by living in the State of Israel compared to Diaspora: We are free from certain kinds of dangers — even though living here amplifies others. There are relative socioeconomic advantages to living in a Jewish State — even as there are undoubtedly relative socioeconomic disadvantages. Which is to say that Zionism is meant to reduce (not eliminate) certain headaches that come with being Jewish, freeing up communal energy to tackle issues that we couldn’t begin to address while living in somebody else’s world.5

Again, Zionism could never purport to be utopian in the sense of eliminating danger, friction, and uncertainty. And Judaism doesn’t exactly promise us a life free from those things: Per Maimonides, there is no distinction between the Messianic Era and an unredeemed world except insofar as the Jewish people won’t be oppressed by foreign nations.6 But somewhere along the line, we’ve made a fetish of safety, simplicity, and certainty — and we’ve assumed that it’s the State of Israel’s job to provide us with those things.

It isn’t.

The job of the State is to put us in the best possible position to fulfill our covenantal obligations towards God, towards one another, and towards all of humanity. Again, that includes making us safer — but the State does not and cannot guarantee that we will be safe.

***

Isaiah Berlin argues that Israel’s value is as state for Jews (as opposed to being a Jewish state). His Zionism does not aim at exceptionalism — quite to the contrary, he aims at normality. It is enough for Israel to simply be a place where Jews govern themselves and speak their own language… just like the French, the Japanese, the Ethiopians, and the Albanians.

In moments of exhaustion, I feel tempted by this argument. It sure would be nice to have a room of one’s own and leave it at that.

But that’s not the mission we were given.

If the State of Israel provides a measure of normalcy and a modicum of respite — it’s as a precondition for something else.

The State of Israel matters because this is the only place where a critical mass of Jews can live together and articulate — in words and in deeds — what it means to live Jewishly as a people.

That’s why we’re here.

VIII.

After destroying Lachish and kidnapping those who survived the massacre, Sennacherib laid siege to Jerusalem. The Bible tells us that Hezekiah was saved by a miracle — that an angel came and struck Sennacherib’s entire army dead.7

At that moment, Jewish history was at its apex. Says the Talmud, God was poised to brand Sennacherib as Gog and Magog and designate Hezekiah as the Messiah.8 History was about to reach its End.

But that didn’t happen.

Because when Hezekiah looked out at the decimated Assyrian army, he didn’t lift up his voice and sing out to God.

His sin wasn’t ingratitude. It wasn’t pride. He just didn’t sing.

That was perfectly understandable. Adorno famously claimed that writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbarism; to sing after Lachish is no less blasphemous. Yes, Jerusalem was spared — but how could anyone possibly hope to lift up their voices as their families were being disappeared into the Assyrian Empire?

Nevertheless and impossible as it sounds, that seems to be the entire ballgame. All the infrastructure that we put in place; all our efforts to make bodies safer, to weave Jewishness into the fabric of our lives; all the blood, sweat, and tears we pour into this place; it’s all there so that we can sing together — as a chorus — through words, melodies, and deeds… even while living under threat and under fire.

The contrapuntal symphony that is supposed to play out every single day — commuters on their way to the office, volunteers heading to the front, children running around in the park, leaders and builders and doers getting their hands dirty, and even mourners, shattered — this is supposed to be the purest and most primal expression of who we are, what we stand for, and what we believe in.

Everything else — truly everything — is a means to that end.

Sing, dammit. Sing.

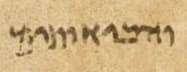

The Lachish Reliefs are the second-oldest surviving depiction of Jews. The oldest surviving depiction is located in the same gallery, barely fifty meters away. Dated to 825 BCE, the so-called Black Obelisk of Shalmanezer III depicts an Israelite king (likely Jehu) bowing down to an Assyrian monarch:

The Judaea Capta coins, in turn, are either the third or fourth oldest surviving visual depictions of Jew (depending whether you count coinage from the Herodian monarchs in this analysis). But all of this is to say that my principal ability to visually access my people’s ancient history and heritage is in seeing how their oppressors depicted them — through representations seeking to show my people in a state of humiliation and degradation.

You could try to argue that great isn’t the same as perfect; and great as our ancestors may have been, they surely weren’t perfect. Fair enough. But Hezekiah is considered as close to a paragon as anything that Jewish history produced; if he still wasn’t good enough, it’s hard to imagine that we can realistically do to immunize us from the world as it is.

See Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Avodat Kochavim 1:1.

A culture, a set of beliefs, or practices that is antagonistic towards (or merely even indifferent towards) Jewish sovereignty in the Jewish homeland may be many things — but it is categorically not Judaism.

Jews can and should have all sorts of opinions about how Jewish sovereignty is being presently exercised in the Jewish homeland. But an unwillingness to engage constructively with it from within a covenantal framework (i.e., from the shared premise that Jewish sovereignty in the Jewish homeland is necessary and good and important) is to effectively remove oneself from the covenantal project of being Jewish.

It’s hard to improve on what Rousseau wrote back in 1762:

Those among us who have the opportunity of talking with Jews are little better off. These unhappy people feel that they are in our power; the tyranny they have suffered makes them timid […] will they dare to run the risk of an outcry against blasphemy? […] The more learned, the more enlightened they are, the more cautious. You may convert some poor wretch whom you have paid to slander his religion; you get some wretched old-clothes-man to speak, and he says what you want; you may triumph over their ignorance and cowardice, while all the time their men of learning are laughing at your stupidity. But do you think you would get off so easily in any place where they knew they were safe! At the Sorbonne it is plain that the Messianic prophecies refer to Jesus Christ. Among the rabbis of Amsterdam it is just as clear that they have nothing to do with him. I do not think I have ever heard the arguments of the Jews as to why they should not have a free state, schools and universities, where they can speak and argue without danger. Then alone can we know what they have to say.

This passage — taken from Rousseau’s controversial text Emile, Or Treatise on Education — both makes my point while also demonstrating how easy it is to miss the mark on why the pursuit of safety matters:

Then as now, Diaspora Jews — like any minority group — had to think hard about speaking up, lest they cause offense to the dominant culture. Conversely, in a Jewish State, we don’t need to fear offending the ruling authorities or their fellow citizens when it comes to talking about Jewishness and Judaism — we don’t need to pull our punches in that respect. Thus, statehood gives us the opportunity to speak freely as Jews and without self-censorship (let alone external censorship). Relative safety is thus a necessary precondition — a means to the end goal of speaking up and living loudly.

So far so good. And yet the passage — shot through with discussions about safety and vulnerability — also lends itself to the erroneous conclusion that a state guarantees safety against all dangers.

Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Malachim u’Milchamot 12:2. (“The Sages said that there is no difference between this world and the time of the Messiah, except only the dominion of foreign empire.”) [the translation is my own]

See II Kings 18-19; Isaiah 36-37. The Lachish Reliefs are horrifying for what they depict. And yet, consider what they omit: Sennacherib — commander of the greatest army of the ancient world — decorated his palace with a single battle scene… one which shows his armies destroying a garrison in southern Judea... not Jerusalem. And in this sense, Lachish Reliefs shows what Sennacherib wasn’t able to do — they attest to the fact that he came up short.

Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sanhedrin 94a.