The Granaries of Jerusalem

"Hunger allows no choice / To the citizen or the police; / We must love one another or die."

Nearly two thousand years ago, the Jewish people found themselves on the wrong side of a fight with the Roman Empire. Determined to destroy what little remained of Jewish autonomy and identity, the Romans brought the full weight of their cultural, economic, and military power to bear against that task and laid siege to Jerusalem.

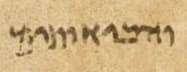

According to the Talmud,1 a group of civically minded Jewish philanthropists gathered together to consider how they’d help their people withstand the external threats and survive the siege. And — says the Talmud — they pooled together their hard-earned resources:

One donated storehouses full of grain. Another contributed a large supply of oil. Another gave copious amounts of kindling and fuel. Their collective generosity would have allowed Jerusalem to withstand a siege for many years. In short, this was collaborative philanthropy working exactly as it was supposed to.

But then as now, the Jewish people were bitterly divided. Despite being literally under siege, Jerusalem was split between multiple factions — groups that sharply disagreed about the future of Judaism and Jewishness. The arguments between those factions simmered, escalated, and boiled over into civil war, and ultimately, the precious granaries of Jerusalem were caught in the crossfire and burned to the ground.

With its food destroyed, Jerusalem succumbed to famine — and the Romans quickly sacked the hungry city, destroyed the Jewish temple, and exiled the Jewish people from their historical homeland.

***

Two thousand years later and the Jewish people are still living under siege and under fire. And though the technology may have been updated, we’re still relying on the same basic strategies. If my ancestors depended on well-stocked granaries, my family and I are protected by Iron Dome, bomb shelters, and the like. I thank God for that. American Jews can likewise look to security guards, bulletproof glass, and a wide range of institutions and programming that make it harder for people to hurt Jews. I thank God for that too.

But instead of using this hard-earned margin of safety productively and for high purpose, we’d prefer to tear ourselves to pieces, even as our enemies sharpen their literal knives. The contemporary Jewish community — whether in Israel or in America — makes first century Judaea look like a model of civic harmony: We have Jews resorting to violence against other Jews. We have Jews actively trying to sanction other Jews. We have Jews trying to cancel and exclude other Jews. We have Jews who are keen to sacrifice other Jews for political advantage. We have Jewish politicians who are gleefully setting their own countries on fire.

Two thousand years have passed and nothing has changed. We know how to feed a hungry people when supply chains are cut off. We know what it takes to intercept a ballistic missile — and I’ve seen it happen with my own two eyes. I don’t take these things for granted and neither should you… our lives literally depend on them. But I ask in all seriousness: To what end? What difference does any of this make if we’re destroying ourselves internally and trying to rip each other’s throats out?

We have the intellectual, social, and economic capacity to protect Jewish bodies from any external threat. We dream up extraordinary infrastructure. We gather the resources and summon the willpower to build it. And we execute pretty much flawlessly.

But then we stop there and pretend to be shocked and appalled when our granaries go up in flames.

***

I used to believe that this had a benign explanation: That we know how to protect Jewish bodies, but we haven’t the foggiest idea how to cultivate Jewish community

I was naïve.

If we have figured out how to shoot missiles out of the sky but we’re still taking shots at one another, we’re seeing the law of revealed preferences at work. Our success at protecting Jewish bodies is self-incriminating, proving that our descent into factionalism is a choice. We are telegraphing our preferences loudly and unmistakably: We have no interest whatsoever in cultivating Jewish community.

Please, let’s for a change be honest with ourselves and just admit it: Our supposed fear of the Romans, of the Iranians, the Qataris, of European taxi drivers, or of a bunch of TikTok-addled Gen. Z slacktivists is dwarfed by our disdain for and fear of our fellow Jews. As we’ve shown time and again, we’d rather die alone than live in community with one another other.

And we know exactly what we’re doing.

We choose factionalism over community despite knowing full well that we will be overrun by our enemies, because we understand what it takes to live in community with one another.

And in our defense… I sort of get it.

Intractable difference is a fixed cost of being human. And forging a community under such circumstances is a hard and painful process. Look what happens when you try to do something with the people in your innermost circle… the ones who care about you the most or the ones who you care about the most. Seventy percent of family businesses don’t make it to the second generation. Too many marriages fail. The Talmud drives the point home when it describes the process by which two individuals come together to create a loving marriage as being as difficult as the Splitting of the Sea.2 The choice of words is telling: We are meant to see a loving marriage as literally miraculous, literally supernatural. The fact that two discrete individuals can create an enduring bond defies the natural order of things.

Why? Because there are no shortcuts. Because there is no way to bond with another person through hollow platitudes and empty sloganeering; you cannot forge a cohesive group by highlighting a common enemy. Because there is no sugarcoating the fact that a collective — whether a marriage of two, a family of five, a clan of seventy — requires mutual sacrifice and self-contraction on a daily basis. And these are things that we as a species are ill-equipped to do.

And now consider that same process, at scale, with an innumerable mass of people divided by innumerable issues — not stuff like whether capital gains should be taxed at 20% or 35% — but stuff that goes to core of identity, morality, and worldview… the things that are insusceptible to negotiation and compromise. Try forging a community with people you consider to be sinners, fundamentalists, parasites, vultures, bigots, or snobs (and who think the exact same of you). How, how could you even contemplate the process of living together, of deciding together, of moving together under such circumstances?

***

Many years ago, it might have been possible to retreat to an insular and homogenous community. But that’s simply impossible nowadays, in this deeply interconnected and interdependent world. Intractable difference with our neighbors is unavoidable and inescapable.

And so some of us resort to conquest. They try to suppress the other side, or try to convert the other side — strategies that are as fanciful as they are immoral. As my friend and teacher Dr. Yoav Heller puts it: Nobody is going anywhere. The thorniest issues remain in a pretty stable equipoise. And we need to accept that intractable difference is a fixed cost of being a human, and there’s nothing we can do about it.

And so if we can’t retreat and if we can’t conquer, we’ve really got no choice but to try and live together. In other words, impossible as it may seem, there’s no moral alternative to community.

***

… But in spite of all that I’ve just said, we cannot afford to be fatalistic about things. The ubiquity of happy and loving marriages is proof that miracles in fact exist: The sea splits anew every single day. We can shoot missiles out of the sky. We have every reason to believe that we can — and therefore must — escape the gravitational pull of human history.

My hope is to try and prove that burnt granaries are a choice — not our destiny. And thankfully, there are people who are trying to show you can form a community — one that leverages pluralism to create a common sense of purpose, destiny and narrative — even in the face of external threats and internal factionalism. There are programs that are working to show that we can work together not merely in spite of intractable difference, but through intractable difference. It’s hard work and success is by no means guaranteed, but I’m encouraged by what I’m seeing.

I’ve written previously about MAOZ. And this is a huge part of why MAOZ matters. MAOZ doesn’t simply accelerate leaders from across different communities and sectors — it also works to build trust between them. It gives those leaders a context where they can talk frankly and openly about what divides them: A place where they can bring their whole and authentic selves… and still continue to trust one another, work together, and ultimately create change together.

I’ve also written about the Rivon Revi’i (for those unfamiliar, this article is well worth your while). The Rivon likewise aims at a future forged in courage, mutuality, and pluralism — it aims to demonstrate that a new type of politics is possible; that there is appetite among the grassroots to engage across communal and sector lines. And indeed, there are thousands of activists who come together regularly despite disagreeing passionately with each other, to have conversations with one another… to challenge and be challenged… to learn and to teach. Importantly, and in contrast to many other NGOs which engage in similar work, the Rivon doesn’t seek dialogue for dialogue’s sake — and it does not seek to force compromises that leave everyone dissatisfied or settle on a hollow consensus. Rather, they seek to create a shared pluralistic vision for Israeli society, which is a product of a process whereby everyone brings their authentic self but also has to sacrifice something meaningful.

But that’s just the tip of the iceberg — there is a growing field of leaders here who are working on radical models that do the hard work of cultivating community. Could this be a path forward for Israel? I’m certainly betting on it. And could these methodologies offer solutions for America, and for other similarly divided communities? I surely hope so too.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. I couldn’t possibly tell you that we’ve figured it out. This is risky and uncertain business. But, again, what’s the alternative?

… Even as I smell the smoke from the granaries — yours, mine, ours — I know this much:

There is much that divides us.

But I can’t do it without you.

And you can’t do it without me.

So let’s try together.

See Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Gittin 56a. And although Talmudic truth does not necessarily depend on historicity, it is worth noting that the basic elements of this narrative are corroborated by contemporaneous primary sources. See Josephus, Wars of the Jews V.1.4.

See Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sotah 2a.

Very powerful piece, Daniel. Two related thoughts, which provide silver linings:

1. Sociological theory suggests that you can't really infer individual preferences from collective action. It is certainly very possible for a group of people, each of whom is deeply wants to build and sustain a strong community, to fail to build and/or sustain such community. The failure comes from various challenges associated with aggregating preferences, especially when the specifics aren't so compatible (you want a mechitzah down the middle of your shul; they want one in the back...)

2. The survival of Jewish identity over the millennia despite the absence of political power can be ascribed in part to the development of a model of identity that is highly nonhierarchical and decentralized, in the sense that in the first instance, all you need is a small critical mass (a minyan...) of fellow Jews, historical links to other Jewish communities, and a commitment to a few basic practices and beliefs, and no one else can challenge your Jewishness. This makes for an extraordinarily *robust* Jewish people in the face of threats, but the flipside is that we're cantankerous and prone to factionalism. This doesn't make the challenge you identified any easier, but I think it suggests that the challenge derives from a positive source and isn't just a defect. And I think it means we have more to work with than we would if people weren't so invested in their Jewishness, even if they have different ideas about what that Jewishness means.

Good set of questions here, which I've been thinking about too. My current thesis is that the more we centralize power, the more we will fight over it. If anything, that is the lesson I take out of our history: when we build temples they will be destroyed. When we centralize the government in Jerusalem it will be corrupted.

We survived millennia because we learned that the People of Israel were meant to live as tribes loosely united, where communities could self-define, yet come together when addressing a common threat. That way, each community could dream its own future without fear of coercion by another. That way, each community could know its obligations and bear its own responsibility. The propagandist writing of the time of the Judges has been misread: “In those days there was no king in Israel; everyone did what was right in his own eyes” is an ideal to strive for, not a reason to set up a Kingdom.