I.

One in five. Two in twelve. One in four.

This is the story of the Jewish people:

Tradition tells us that after an escalating series of catastrophes, a mighty pharaoh emancipated a teeming nation of serfs, allowing them to remain in his empire on equal footing with their neighbors. Most of the freed slaves opted to remain in Egypt and were lost to history. Only one in five chose otherwise, leaving Egypt and walking into a barren wilderness in search of an uncertain future.

After King David pacified the Holy Land and after King Solomon built the Holy Temple, it all fell apart. Solomon’s newly crowned son showed himself to be a callow and inexperienced leader. Rather than weathering the storm and waiting for their king to mature, the majority of the Jews opted out of the covenant and forsook the Davidic line. The people enthroned a rebel pretender and exchanged God for graven images. Only two tribes — Judah and Benjamin — remained loyal to God and His anointed king. The ten rebellious tribes are no more; only the two loyal ones endure.

Four great rabbis sought to live in truth; only one proved capable of doing so. This is the parable of Pardes. Seeing the world as it really is proved enough to break even the strongest of leaders: One lost his mind, one lost his life, and one lost his faith. Only one of them walked out unscathed.

One in five. Two in twelve. One in four.

These are the Jews who lived. These are the Jews who endured. These are the Jews of the Jews.

II.

I have been asked by people much smarter and wiser than I am why there is such limited support among American Jews for Zionism and the State of Israel.

You could try to challenge the premise of the question by pointing out that large majorities of American Jews identify as Zionists or that most Jews express an affinity with the State of Israel. There are Jews bravely putting their bodies on the line and who are paying a real price for their solidarity with their Israeli brethren. And yet these brave souls stand largely alone. Polls can’t mask what we know to be true: There aren’t enough Jews who are committed to our national project and collective destiny.1

You could also try to offer psychological, sociological, or political answers to this question. You might argue, for example, that the Jewish people are so traumatized by millennia of persecution that they believe — on some deeply internalized level — that they aren’t deserving of sovereignty and independence. Or that lukewarm support for Israel among some American Jews suggests that they believe, deep down, that they are only conditionally tolerated in the United States… that they feel a need to prove themselves loyal and worthy Americans.2

But it would be a mistake to ask a psychologist or a political scientist or an historian to answer this question. Because to ask why there is limited Jewish support for Israel is like wondering why do bad things happen to good people? or asking why does evil exist? — these are fundamentally religious questions that need to be thought about within and through a religious framework.

It’s not that religion actually provides an answer to these questions; these are not phenomena susceptible to easy explanations (or any explanations, for that matter). Rather, religion teaches us how to live with uncertainty, unanswerable questions, and unattainable goals — i.e., how to exist as limited, bounded beings. Religion does not necessarily provide resolution; sometimes all we can ask of it is to help us better frame an irresolvable problem and then to help us consider our responsibility as relates to it.

And so if we consider the lack of Jewish support for Israel through the lens of faith and religion, something approximating an insight begins to emerge. The stories of the Exodus, Jeroboam, and Pardes point us towards a truth, difficult yet inescapable…

The religious journey of the Jewish people is a fugue: A contrapuntal song — at times nightmarish, at times sublime — consisting of the same theme presented, developed, re-presented and re-developed again and again and again. It can only be understood as the story of the Jews of the Jews. Our history is that of the minority of the minority, a remnant of the remnant — the people who were brave enough to stand in countercultural distinction to the rest of their group and who walked, bravely, into the unknown and uncertain future.

God chose one nation out of seventy. Not because they were better. Not because they were deserving. Not because God needed them. God simply chose a specific people to do a specific job.

And our ancestors having been chosen for that job, we are asked — in every generation — to choose again, ourselves.

The numbers speak for themselves: One in five. Two in twelve. One in four.

The Jews of the Jews may be enough to change the world: We have done an awful lot with just the dust of Jacob… we can do even more with simply a quarter of Israel.

… But my God — I surely wish that more of us answered the call.

III.

The essence of living faithfully is (to paraphrase Justice Scalia) having the courage to have your wisdom regarded as stupidity and having the strength to suffer the contempt of the sophisticated world.

It’s not easy to do this. Even before October 7th, it took a lot of courage to stand with Israel. It’s especially daunting to do so lately.

The world has gleefully lapped up the fake news, the lies, and the outright blood libels from the chattering classes — and they’ve concluded that Israel is a genocidal state and an apartheid entity. They are setting elderly Jews on fire in Colorado; they are gunning down young Jews in the streets of Washington D.C. And the murderers are being cheered loudly.

I will not make the mistake of saying that Israel stands completely alone. We have true friends and steadfast allies. And we must strive every day to be worthy of this love, faith, and solidarity.

But as far as the Jewish community itself is concerned, our history suggests that it is only the Jews of the Jews who will remain committed to our communal destiny and our collective mission. Because it requires real courage to step up to the plate; to be Jewish is to put yourself in the crosshairs. It often seems rational to walk away from the world-historical Jewish mission and exchange it for something that seems quite a bit less daunting and quite a bit more attainable.

Only a minority left Egypt. Only a remnant remained loyal to the House of David. Only a fragment could live in truth.

Perhaps so too with the State of Israel. Perhaps so too with Zionism.

But I surely hope not.

IV.

When Jewish history hangs in the balance, when the world presents the Jews of the Jews with a time for choosing, what is our obligation towards those who’d rather not come along for the ride?

Jewish history offers two paradigms. Both require our consideration:

A. The Wilderness

Following the Exodus, Moses was presented with incontrovertible evidence of the Jewish people’s corruption. And God presented him with an opportunity for a culling. God offered to destroy the Children of Israel and to start again with Moses as its patriarch.

Moses refused the offer. Twice.

He begged for the people. He demanded their survival. He fought for Jewish continuity. He prayed for mercy. And the catastrophe was averted.

… Think how counterintuitive that is. Consider how radical it was that Moses sought to preserve the Jewish people in toto. Moses’s choice ensured that the Jewish people would endure — including those inclined towards idolatry, faithlessness, and cynicism. Moses’s choice preserved the wrongdoers alongside the righteous. From a perspective of statecraft and brutal efficiency, it’s not clear that this was the right decision: A committed remnant could have gone so much further and so much faster.

It’s much easier to build minimum viable products for utopia if you’re not diverting resources to try and include those who don’t want to be included. Every minute wasted trying to bring along a skeptic is a minute that could have been used to try and build infrastructure, forge new alliances, or strengthen institutions.

But that’s not what Moses did.

B. The Siege

The Talmud tells us that at the height of the Roman siege of Jerusalem — when the city’s defeat was all but certain — the great sage Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai managed to sneak out of the city and obtain an audience with the Roman commander, Vespasian.

Rabbi Yochanan managed to win the general’s favor and — when offered a boon — asked to preserve the city of Yavneh and its sages, along with a select number of his fellow rabbis. Vespasian granted this request and the Jewish people lived to fight another day.

It’s difficult to know what to make of this in the final analysis and with the benefit of hindsight. On the one hand, we are here today thanks to Rabbi Yochanan — and maybe we should therefore refrain from second guessing his decisions. But on the other hand, Rabbi Yochanan went where Moses would not: He opted to reboot the Jewish nation with himself and his associates as its patriarchs.

And as the Talmud suggests we ought not live comfortably with that choice. It observes, pointedly and critically, that Rabbi Yochanan could have aimed quite a bit higher. Why didn’t he ask Vespasian to spare the Temple? Why didn’t he try to save the city of Jerusalem? Yes, the scholars were saved and yes, some of our people survived — but what about the rest of the Jews who were left behind to be starved, tortured, murdered, abused, and sold into slavery?

***

If I had to choose, my sympathies lie much more with Moses, but we dismiss either approach at our peril.

Because it’s easy to know what to do when religious duty, political considerations, and economic self-interest are all in alignment — when each of the plural and complementary systems that humans use to navigate the world all point the same course of action.

The real challenge is what we’re supposed to do when those different systems demand different things of us at the same time. The correct answer depends entirely on which lens you’re using and how you’ve framed the problem: If it’s a religious matter, thou shalt not — if it’s a political matter, thou shalt.

And this is the essential dilemma of Nero’s Arrows: What are we supposed to do when the demands of the Torah are in tension with the responsibilities of statecraft? What happens when your duties as a leader conflict with your familial obligations? What happens when you have a choice to make as relates to the four out of five, the ten out of twelve, or the three out of four? Is it monstrous to walk away from them? Is it pointlessly noble to go down with them?

Teiku.

For now, let the question stand.

V.

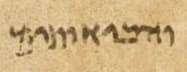

After marveling at what the Jews of the Jews are able to accomplish (who has counted the dust of Jacob and the number of a fourth of Israel?) the prophet Bila’am prayed that he would die the death of an Israelite: Let me die the death of the upright, and may my end be like his!

… What a sad prayer.

As I have learned from the greatest of my teachers: It’s easy to die as a Jew… we do it all the time! The challenge is to live as a Jew. Can you imagine if Bila’am had — instead — not simply prayed for a righteous death but sought the strength to live a righteous life?

It is tempting, in like fashion, to pray for the strength and the courage to live as a Jew of the Jews — for the wherewithal to escape the siege and for the strength to hold fast to what matters even when the world is falling apart.

But I believe that such a prayer would also be a mistake. God gave me the unearned grace to be one of seventy. I don’t — in turn — want to be one of five, two of twelve, or one of four. I don’t want to be numbered in the remnant… I don’t want there to be a remnant!

The fact that our history has been a story of the Jews of the Jews does not mean it will inevitably play out that way. And we shouldn’t embrace that fact that the Jews who have endured to date have been a remnant of the remnant and a minority of the minority. It is monstrously self-defeating to conclude that we are fated to choose and cull and winnow and sift again and again.

Instead, we are called upon to try and work a miracle: That somehow, we will find the strength to count four fourths of Israel… that one becomes two becomes three becomes four becomes One.

Because if and when we succeed at raising the yield — of increasing the number of Jews who opt in and who choose their chosen mission — then, and only then, do we have any hope of bringing this fugue to an end and singing before Him a different song:

Hallelujah.

Again, I am awed by the brave and committed people who give tzedakah, who march in solidarity, and who speak out publicly. But I am saddened to see that this level of commitment is so unevenly distributed; we as a people are not nearly as mobilized as we could be… or should be.

Indeed, I have heard some argue that non-Jewish Americans can afford to be unapologetically vocal in their support of Israel than their Jewish counterparts because nobody can question their patriotic bona fides.